the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 License.

the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 License.

Optimized procedure for the determination of alkylamines in airborne particulate matter of anthropized areas

Davide Spolaor

Lidia Soldà

Gianni Formenton

Marco Roverso

Denis Badocco

Sara Bogialli

Fazel A. Monikh

Due to their role in the formation of secondary aerosol, the concentrations of the most abundant aliphatic amines (methylamine (MA), dimethylamine (DMA), ethylamine (EA), diethylamine (DEA), propylamine (PA), and butylamine (BA)) present in the aerosol of a very anthropized area were measured by an optimized analytical procedure. PM10 samples were collected in the tanning district of Vicenza (in the Po Valley, northern Italy) in autumn 2020. Alkylamines were extracted in water and converted to carbamates through derivatization with Fmoc-OSu (9-fluorenylmethoxycarbonyl-N-hydroxysuccinimide) for subsequent determination by ultra-high-performance liquid chromatography (UHPLC) with fluorescence detection. The procedure has been optimized, obtaining very satisfactory analytical performances: limits of detection (LODs) were in the range of 0.09–0.26 ng m−3, with an average uncertainty of 3.4 % and recoveries of 95 %–101 %. The mean total concentration of the six amines measured in this study was 37±17 ng m−3, with DMA making the largest contribution. The proposed procedure may contribute to a better characterization of the local aerosol. In our preliminary investigation, Pearson's correlation test showed that amines correlate strongly with each other and with secondary inorganic ions (NH, NO, and SO), confirming that they compete with ammonia in the acid–base atmospheric processes that lead to the formation of nitrate and sulfate particles. The developed method allows us to gather critical information about the load of aliphatic amines in particulate matter (PM) to gain more insights into the sources and fate of these chemicals in the atmosphere.

- Article

(963 KB) - Full-text XML

-

Supplement

(1716 KB) - BibTeX

- EndNote

Atmospheric particulate matter (PM) is the subject of many discussions about the health of humans and ecosystems. A polluted atmosphere contains hundreds of organic and inorganic compounds that are involved in the formation of secondary aerosols and contribute to their toxicity. Atmospheric amines could be especially important due to their acid-neutralizing capacity. These amines are derivatives of ammonia with one or more hydrogen atoms replaced by an alkyl or aryl group. Like ammonia, they are hydrophilic basic compounds that exist in the atmosphere in both gaseous and particulate phases. Amines could undergo rapid acid–base reactions with acids such as H2SO4 and HNO3, similar to the transformation that occurs for ammonia itself (Ge et al., 2011b). Theoretical and experimental studies also show that alkylamines can react with ammonium sulfate and ammonium bisulfate clusters, resulting in the displacement of ammonium with aminium (Bzdek et al., 2010; Qiu et al., 2011). Amines are also believed to play an important role in stabilizing sulfuric acid clusters in the early stages of new particle formation (NPF) (Loukonen et al., 2010; Almeida et al., 2013; Yao et al., 2018; Xiao et al., 2021). They can also contribute to the production of secondary organic aerosol (SOA) by reacting with organic acids and oxidants (e.g., O3 or •NO3) (Denkenberger et al., 2007; Tang et al., 2013; Nielsen et al., 2012; Malloy et al., 2009). Most amines are toxic and irritants to the eyes, skin, and mucous membranes and some of their oxidation products can also be carcinogenic (e.g., nitrosamines) (Lee and Wexler, 2013). The most common organic amines found in the atmosphere are C1–C6 alkylamines, which can be emitted from a variety of anthropogenic and natural sources (Ge et al., 2011a). The main natural sources include biomass burning and biological activity, in particular from marine environments (van Pinxteren et al., 2019; Xie et al., 2018). Animal husbandry is one of the main anthropogenic sources of atmospheric amines, along with various industrial activities, in particular the food industry. Other anthropogenic sources include fuel combustion (Shen et al., 2017), vehicular traffic, composting, the treatment of industrial waste, and the combustion of tobacco (Ge at al., 2011a). Tanneries may also represent a significant source (reference reports in JRC, 2013) as amines are formed and released in the atmosphere both in the preliminary steps of the tanning process (storage, desalting, and pealing of the raw hide) and in the wastewater treatment plants. In urban areas, anthropogenic nonagricultural sources could represent the main contribution to amine emission (Shen et al., 2017; Cheng et al., 2020; Liu et al., 2022). Furthermore, emerging emission sources of amines have been associated with their use in the CO2 capture processes and, possibly, in catalytic processes for the reduction of NOx emissions from engines (Ge et al., 2011a; Muthiya et al., 2022; Stanciulescu et al., 2010).

Measurement of the ambient concentrations of atmospheric amines is challenging due to their high volatility and polarity. Common techniques for the determination of low-molecular-weight alkylamines are gas chromatography (GC), high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC), and ion chromatography (IC), coupled with different detectors. In direct analysis by IC, the process of separation and quantification of all analytes is often difficult due to interference from other cations (e.g., sodium or potassium) and the difficulty to separate some of the amines (e.g., diethylamine and trimethylamine) (VandenBoer et al., 2012; Huang et al., 2014; Zhou et al., 2018; Feng et al., 2020). These problems can be addressed by carefully adjusting the temperature and the elution program or by modifying the retention times of the interfering ions with an eluent additive (Place et al., 2017; Feng et al., 2020). Proton-transfer-reaction mass spectrometry (PTR-MS) is the elective technique for the direct (and online) determination of amines in the gas phase (Wang et al., 2020; Chang et al., 2022) with elevated analytical performances (fast response, high sensitivity). Unfortunately, it fails for the separation of amines with the same molecular mass (i.e., dimethylamine / ethylamine (DMA / EA) and propylamine / trimethylamine (PA / TMA)). This drawback is also reported in the direct HPLC-MS analysis of amines (Kieloaho et al., 2013; Tzitzikalaki et al., 2021), in view of the difficulties in separating these species (non-derivatized, in the absence of a suitable MS2 detection system). Direct analyses of amines can also be performed using GC (Bai et al., 2019). However, the polar nature of small aliphatic amines makes these analyses unfavorable due to the adsorption and decomposition of the solute in the column, resulting in peak tailing and analyte losses.

Because of the poor results often obtained with direct analyses of amines, the derivatization of the target analytes is recommended. Organic amines can be derivatized with various methods such as acylation, carbamate formation, Schiff base formation, and silylation (Płotka-Wasylka et al., 2015). Among these methods, acylation and carbamate formation are the ones most commonly used, because they allow for a simple and fast derivatization step, where amines are easily derivatized in aqueous solutions and mild conditions. The derivatization is usually followed by a GC or HPLC separation. Derivatization can also be used to add a chromophore (or a fluorophore) to derivatized analytes, allowing both improved chromatographic performance and the detection by UV–Vis absorption or fluorescence (Płotka-Wasylka et al., 2015; Szulejko and Kim, 2014) with significantly higher sensitivities with respect to the conventional detection of non-derivatized species. In this work, a simple and sensitive analytical method for the determination of aliphatic amines contained in atmospheric PM has been developed and validated. It makes use of a water extraction of amines, their derivatization by Fmoc-OSu (9-fluorenylmethoxycarbonyl-N-hydroxysuccinimide), and their instrumental analysis by UHPLC with fluorescence detection (FLD). The procedure has been applied for the determination of six volatile aliphatic amines (methylamine (MA), dimethylamine (DMA), ethylamine (EA), diethylamine (DEA), propylamine (PA), and butylamine (BA)) contained (as aminium salts) in PM10 samples of a highly anthropized area. The results are also preliminarily discussed to assess the contribution of aliphatic amines in the formation of secondary aerosol.

2.1 Chemicals

Ultrapure water (18.2 MΩ cm, ELGA LabWater PURELAB Chorus 1 Complete) and 37 % HCl solution (ACS reagent, Riedel-de Haën) were used for the extraction of the analytes; Fmoc-OSu (9-fluorenylmethoxycarbonyl-N-hydroxysuccinimide, Sigma-Aldrich), acetonitrile (>99.95 %, CARLO ERBA Reagents), sodium tetraborate (sodium tetraborate decahydrate, Normapur), and NaOH (>97 %, ACS reagent, Sigma-Aldrich) were used for the derivatization step. Methylamine (MA), dimethylamine (DMA), ethylamine (EA), diethylamine (DEA), and propylamine (PA) were purchased as hydrochloride salt (>98 %, Sigma-Aldrich), while butylamine was purchased as pure liquid (99.5 %, Sigma-Aldrich).

2.2 Aerosol sampling

The sampling campaign was carried out in the Chiampo Valley (Po Valley, northern Italy), an area located near Vicenza and characterized by the presence of numerous leather industries (tanning district). PM10 samples were collected for 24 h, and PM10 mass concentrations were directly measured using an automated beta attenuation analyzer (SWAM 5a Monitor, FAI Instruments, Italy), working at a constant flow rate of 2.3 m3 h−1 and equipped with 47 mm quartz filters (Whatman, QM-A quartz filters, particle retention rating 98 % at 2.2 µm). The filters were not treated before use; acceptable blank values were always obtained (organic carbon (OC) <0.4 µg m−3, DMA ≪ LOD). This sampling and measurement procedure (implemented in the air quality monitoring network of the Regional Agency for Environmental Protection and Prevention in the Veneto, ARPAV) is the standardized “Ambient Air – Automated measuring system for the measurements of the concentration of particulate matter (PM10; PM2.5)” (EN 16450:2017). It is worth noting that artifacts can occur in the sampling of aliphatic amines, as described by Shen et al. (2017). They are mainly due to gas–particle phase transfers and some structure rearrangements, although different hypotheses regarding DEA are proposed. However, in studies in which gaseous amines are sampled on acidified quartz filters, significant absorption on untreated filters used for the PM sampling seems to be excluded (Chen et al., 2022). We did not estimate these artifacts, but considering that amines are present in PM as aminium salts, the sampling losses of these low-volatility compounds were probably limited. In this regard, more in-depth analytical studies would be desirable.

The sampling campaign was conducted in three different areas of the Chiampo Valley over a 2-month period, from 18 September to 7 October 2020 (site of Montebello), from 13 October to 28 October 2020 (site of Montorso), and from 30 October to 18 November 2020 (site of Trissino). A total of 53 PM10 samples were collected. Filter samples were kept at −20 ∘C until further analysis. Analyses of water-soluble ions (by ion chromatography), organic carbon, and elemental carbon (by Sunset OC/EC analyzer) were also performed using well-established procedures (Giorio et al., 2022; Khan et al., 2016).

2.3 Sample preparation

Analytes were extracted from a portion of the filter () with 3 mL of a 0.1 M HCl solution in ultrapure water followed by sonication for 10 min at a temperature below 25 ∘C. A volume of 1.5 mL of the extract was then filtered (PTFE membrane, 0.2 µm pore size) inside a 1.5 mL test tube and stored for further analysis in a freezer at −18 ∘C. The derivatization reagent was prepared by dissolving a few milligrams of Fmoc-OSu in acetonitrile to obtain a concentration of 8.9 mM (3 g L−1). Borate buffer (0.13 M) was prepared by dissolving 5 g of sodium tetraborate in 100 mL of ultrapure water. An aliquot of 300 µL of the sample solution was added in a 1.5 mL test tube and neutralized by adding 5 µL of a 6 M NaOH solution. Then 150 µL of the borate buffer and 250 µL of the derivatization reagent were added to the solution (pH ≈9). The mixture was stirred for about 30 s and allowed to react for 10 min at 50 ∘C using a thermostatic heating block.

2.4 Instrumental analysis

The solution containing the derivatized analytes was injected into an HPLC (LC-20AD XR Shimadzu; Canby, OR, USA) equipped with an autosampler (SIL-20AC XR Shimadzu, injection volume 5 µL) and a fluorescence detector (RF-20A XS Shimadzu). Excitation and emission wavelengths were 264 and 313 nm, respectively. The separation was performed using a Luna Omega 1.6 µm Polar C18 column (100×2.1 mm), with a constant flow rate of 0.2 mL min−1 and a column temperature of 30 ∘C. A gradient elution program using acetonitrile (eluent B) and water (eluent A), to which formic acid was added (0.05 %) to both solutions, was optimized and used to separate the derivatized amines. The elution program started with a mixture containing eluent B at 40 %; after 1.5 min, the concentration of B was increased linearly to 60 % in the span of 13.5 min and kept constant for 4 min; then the concentration of B was raised to 100 % in 0.2 min and maintained for 6 min (before returning the system to the initial condition, for a chromatographic run lasting 32 min). Concentrated standard solutions (1 g L−1; for DMA, it corresponds to 22 mM) were prepared by dissolving the hydrochloride salt of the amines in ultrapure water or, in the case of butylamine, by diluting the pure amine. From these solutions, a mixed working standard solution containing all amines was then prepared, each at 10 mg L−1. This solution was diluted to obtain calibration solutions at suitable concentrations (10, 50, 100, and 250 µg L−1). These standards were analyzed in duplicate to obtain the calibration functions. Laboratory blanks consisting of ultrapure water and matrix blanks consisting of aqueous extract of blank quartz filters were treated and analyzed each day as regular samples to control the contribution of both chemicals and filters to the analytical signals. The real sample results were corrected for the matrix blank concentrations.

2.5 Analysis via ESI-QTOF-MS

The possible presence of chromatographic interferences was investigated by analyzing PM10 samples using independent detection techniques. Specifically, three selected PM10 samples were analyzed using the same sample preparation procedure and the same chromatographic method described in Sect. 2.3 and 2.4 but with two different detection systems: fluorescence and electrospray ionization quadrupole/time-of-flight mass spectrometry (ESI-QTOF-MS) (Agilent 6545, mass resolution 35000). The UHPLC-MS analysis was performed with an ESI source, operating in positive acquisition mode. Source parameters were 300 ∘C capillary temperature, 40 a.u. (arbitrary units) sheath gas flow, 300 ∘C sheath gas temperature, 20 a.u. auxiliary gas flow, 350 ∘C auxiliary gas temperature, and 4 kV spray voltage. Data were acquired in the range of 100–1000 (scan rate).

2.6 Statistical analysis

The correlations among the data acquired during the campaign (temperature, relative humidity, atmospheric precipitation, and concentration of atmospheric pollutants – NOx, H2S, and NH3 – Table S1 in the Supplement) and the measured concentrations of PM10 components (elemental and organic carbon, inorganic ions and amines – Tables S2, S3, and S4) were evaluated by Pearson's correlation coefficients. Principal component analysis (PCA) was also performed considering the full set of PM10 samples and species analyzed. Atmospheric parameters such as temperature, relative humidity, and precipitation quantities were used as supplementary variables.

3.1 Optimization of the analytical procedure

The aliphatic amines in the atmospheric particulate matter were determined here by extracting the analytes from the sampling filters and subsequently analyzing by UHPLC-FLD, after a derivatization procedure using Fmoc-OSu. Details regarding these reactions are reported in the literature (Iqbal et al., 2014; Lozanov et al., 2004; Płotka-Wasylka et al., 2015). The advantages of this method consist primarily of its rapidity and simplicity; the amines are readily derivatized in an aqueous alkaline solution with the addition of Fmoc-OSu and are directly injected into the HPLC column without the need for further extraction steps.

It is worth noting that the derivatization step is generally mandatory for the separation of amines via HPLC or GC (Huang et al., 2014), and most derivatizing agents are only suitable for primary and secondary amines, thus precluding the analysis of tertiary amines. However, the derivatization of TMA is possible using Fmoc, but the reaction is very slow (Szulejko et al., 2014), especially in aqueous solutions. As a consequence, only primary and secondary amines can be determined by the present procedure. This is confirmed by the fact that, after adding TMA to a standard solution or to a sample, no peak attributable to TMA was identified in our chromatograms. Moreover, regarding a possible bias in the quantification of DMA (tertiary amines derivatized with Fmoc may dealkylate, yielding a product identical to the derivatized secondary amine), no difference in the peak intensity of DMA was observed.

3.1.1 Optimization of chromatographic conditions

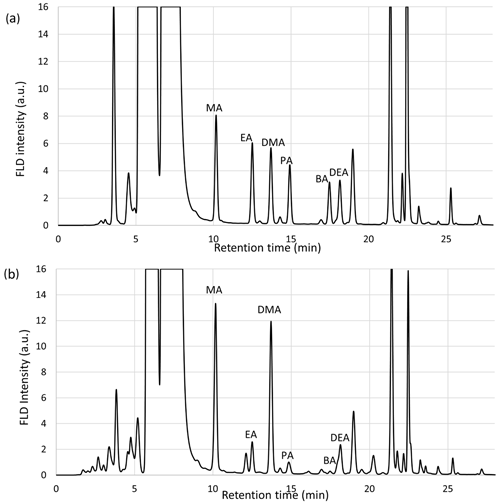

Three RP-C18 columns were preliminarily tested for the UHPLC separation of the six derivatized aliphatic amines (Shimadzu XR-ODS III C18, Phenomenex Luna Omega polar C18, and Phenomenex Kinetex C18), showing similar performances in terms of selectivity. The Luna Omega column was chosen because of its slightly higher efficiency (better peak shape). The elution program (gradient elution using acidic water / acetonitrile for a chromatographic run lasting 32 min) has been optimized to allow for the proper separation of each amine, in particular the ethylamine / dimethylamine and butylamine / diethylamine pairs. The correct separation of methylamine was also problematic due to the presence of a large peak attributable to the by-products of Fmoc-OSu and to the derivatized NH3, which are both present in the solution in large excess. The addition of formic acid in the two solvents (0.05 %) did not have an effect on the retention time of the amines but slightly reduced the retention time of the Fmoc by-products. Changes in the chromatographic method aimed at reducing the elution time without reducing the separation efficiency. Figure 1 shows representative chromatograms obtained for a standard solution (100 µg L−1) and a PM10 sample extract (blank sample chromatogram is reported in Fig. S1 in the Supplement). The order of retention times of Fmoc derivatives is as follows: methylamine (MA, tr=10.1), ethylamine (EA, tr=12.4), dimethylamine (DMA, tr=13.6), propylamine (PA, tr=14.8), butylamine (BA, tr=17.4), and diethylamine (DEA, tr=18.1); the order is the same as that reported in other articles (Shen et al., 2017; Cheng et al., 2020).

3.1.2 Optimization of extraction and derivatization steps

Compared to the procedures of Shen et al. (2017) and Cheng et al. (2020), we added a larger amount of derivatizing agent (250 µL in 700 µL (3.2 mM) instead of just 400 µL in 10 mL (0.36 mM) of Fmoc-OSu in acetonitrile), obtaining stable peaks for each of the six target amines. Therefore, the extraction and reaction steps (time, temperature, and reaction mixture composition) were optimized to gain the maximum recovery for each of the analytes. The extraction was initially tested with ultrapure water, but the addition of hydrochloric acid (0.1 M) showed better results in terms of recoveries (from 80 %–95 % to >95 %), due to the higher water solubility of the aminium ions with respect to the non-protonated amines.

The extraction time was initially set at 20 min, but no significant differences in instrumental signals were observed after reducing it to 10 min (Table S5). The derivatization step was tested at different temperatures (25, 50, and 60 ∘C) and reaction times (5–20 min) (see Table S6 as an example). Using a large excess of Fmoc-OSu, the reaction was quantitative (also for DEA) and very fast even at ambient temperature, as it takes less than 5 min to complete.

However, because the reaction time and temperature affected the amount of unreacted Fmoc in the solution (that may represent a serious chromatographic interference), the reaction was carried out at 50 ∘C, for 10 min, to completely eliminate the chromatographic peak relative to the unreacted Fmoc that co-elutes with the derivatized ethylamine (Table S6). The same results were also obtained using Fmoc-Cl (9-fluorenylmethyl chloroformate) as the derivatizing agent. In conclusion, if compared with most previous published procedures that use a derivatization reagent (Shen et al., 2017; Cheng et al., 2020; Choi et al., 2020; Akyüz, 2008; Majedi and Lee, 2017; Parshintsev et al., 2015), our sample pretreatment does not need successive liquid–liquid extraction or preconcentration steps.

3.2 Method validation

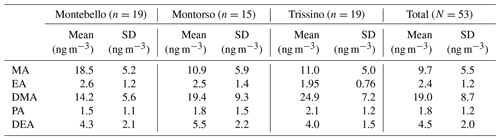

The linearity of the calibration functions, limits of detection (LODs), precision (repeatability), and recoveries of the method were measured experimentally. The calibration functions of the six aliphatic amines (ranged from 0 µg L−1, the solvent blank, to 250 µg L−1) were all assessed as linear after an F test between the linear and quadratic regression variance (α=0.05; ; Fsp<1.85; p>0.2). Repeatability was evaluated as the relative standard deviation (RSD, %) over four equal parts of the same sample (a PM10 filter), each spiked with 15 µL of a mixture containing the six amines at 10 mg L−1 (corresponding to 4.1 ng m−3 in the sampled PM10 and in line with the concentration ranges measured in the real samples). The measured RSD values were less than 5 % for all the amines. The recoveries were evaluated by adding different quantities of a mixture containing each of the six amines at 10 mg L−1 (0, 20, 40, and 60 µL) to four equal parts of the same PM10 sample and determining the slope of each recovery function (Cexperimental vs. Cadded). It was found that the recoveries ranged from 95 % to 101 %, supporting the hypothesis of a negligible effect (bias) of the matrix components on the effective recovery of each analyte at various steps of the procedure, as well as on the instrument response. The limits of detection (LOD) were estimated from the calibration function using the Hubaux–Vos method (Hubaux and Vos, 1970), obtaining values ranging from 1.1 to 3.2 µg L−1, which correspond to an atmospheric concentration of 0.088–0.26 ng m−3. These validation parameters are listed in Table 1.

Table 1Detection limit, recovery, and relative standard deviation of the analytical method developed in this study.

* Estimated by the analysis of a real PM10 sample (spiked, added concentration 4.1 ng m−3 of each amine; n=4).

These performances, compared to the ones obtained by previously developed methods (Huang et al., 2014; Choi et al., 2020; Parshintsev et al., 2015), are characterized by similar or higher LODs, mainly due to lower sampling volume and the absence of a preconcentration step, but also by quantitative recovery functions and good repeatability. Furthermore, our optimized sample preparation procedure allows for the correct quantification of DEA that was not carried out using analogous methods (Shen et al., 2017; Cheng et al., 2020).

Comparison of the results obtained by independent methods

Three samples were analyzed with two different methods as described in Sect. 2.5. In the MS analysis, the signal of the parent ion was used to identify each of the derivatized amines, but it was too low to be used for quantification. As a consequence, the MS signal at 179.0861 (common to each amine, due to the in-source fragmentation of the derivatized analytes and attributable to a residual moiety of the derivatizing agent) was selected for the quantitative MS analysis. Butylamine was used as the internal standard, as it was not present in the analyzed samples. To ensure that each amine was present at a concentration high enough to be quantified, 10 µL of a mixture containing the amines at 10 mg L−1 was added to the three samples (corresponding to 1.8 ng m−3). From the comparison of the results obtained by applying the two different methods (Table S7), it was found that the measured concentrations of the amine derivatives were statistically equivalent and that there was no significant systematic difference between the two detection methods. This result suggests the absence of significant chromatographic interferences (bias) in the optimized UHPLC-FLD analytical method.

3.3 Environmental concentrations of aliphatic amines

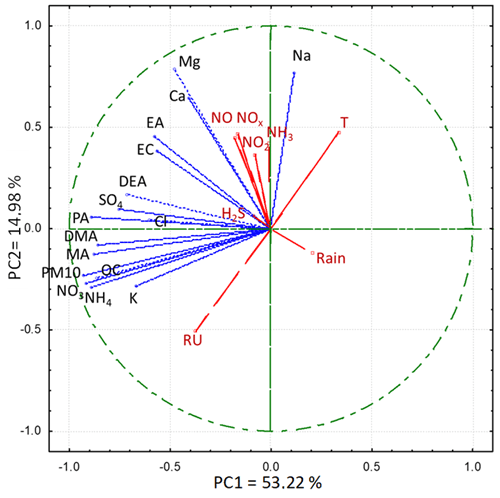

Table 2 shows the mean concentrations of the amines contained in PM10 samples collected in the three sampling sites considered in this study (Montebello, Montorso, and Trissino; Figs. S2–S3). Taking into account the average concentration (± standard deviation) throughout the sampling campaign (53 total samples), the amines present at higher concentrations were dimethylamine (19.0±8.7 ng m−3), methylamine (9.7±5.5 ng m−3), and diethylamine (4.5±2.0 ng m−3), while the butylamine signal was below the limit of detection and therefore not considered in the present discussion. Absolute concentrations in the three sites of EA, PA, and DEA varied very little, while concentrations of MA and DMA were characterized by much wider distributions. The concentration of most of the amines did not show great variations between the three locations considered, except for dimethylamine where the average concentration ranged from 13.7 ng m−3 in Montebello to 24.9 ng m−3 in Trissino (details in the box plots, Fig. S4). The concentrations of aliphatic amines measured in this work are consistent with those described in other studies (Choi et al., 2020; Akyüz, 2008; Feng et al., 2020; Cheng et al., 2020), being in the range of between a few tenths of a nanogram per cubic meter and 1 ng m−3. These studies are here briefly discussed as examples regarding the alkylamine concentrations commonly found in the PM of urbanized areas; more information is summarized in Table S8. In the work of Choi et al. (2020), the concentration of amines (EA, DMA, DEA, PA, and BA) was measured in PM2.5 in the metropolitan area of Seoul (South Korea). The sum of the annual mean concentrations of the target amines was 5.56±2.76 ng m−3 with a low dependence on the sampling season. Consistent with our study, the main contribution was attributed to DMA, while the lowest was attributed to EA. However, the concentrations measured in Seoul were much lower than those measured in the Chiampo Valley (Vicenza, Italy; present study). Cheng et al. (2020) measured EA, DMA, and DEA in Yangzhou, China. They obtained much higher values for EA, 12.58±10.45 ng m−3, but lower for the other two amines. Akyüz (2008) measured amines in PM10 sampled in the Zonguldak industrial area in Türkiye, where pollution is very high due to the production and consumption of coal. Concentrations in the Zonguldak industrial area were rather high for all amines considered (7–9 ng m−3) and higher during winter. In the work of Feng et al. (2020), which was carried out in Shanghai, the amines present at the highest concentrations were found to be DMA and MA, which reached average concentrations around 20 ng m−3. The differences between the measured concentrations in this study and those reported in literature are probably due to the different emission sources present in the Chiampo Valley compared to the other locations. In particular, DMA appears to be present in large quantities in the Chiampo Valley compared to other amines, while BA was almost not detected (<1 ng m−3). The high total concentration of amines could be attributed to the presence of significant emission sources, such as vehicular exhaust or intense industrial activity (tanning industry, in particular). Another potentially important source could be agricultural activity, which is also strongly associated with ammonia emission (Backes et al., 2016). However, recent studies suggest that in urbanized areas the contribution of nonagricultural sources is dominant (Chang et al., 2022). In this connection, we underline that since the 1960s the tanneries of the district have been the main source responsible for the contamination of both the surface/ground waters and the atmosphere of a larger area. In particular, high amounts of H2S and volatile organic compounds (VOCs, mainly toluene, xylenes, ethylacetate, and butylacetate) are emitted into the atmosphere by this industrial activity. This is confirmed by the regional environmental agency (ARPAV) which recently measured high atmospheric levels of H2S (up to 241 µg m−3, daily average, and 1067 µg m−3, hourly average) and estimated that 60 %–88 % of the total VOCs emitted come from the tanneries of the district (ARPAV, 2023; JRC, 2013). Primary aerosol emissions from these tanneries are comparable to those estimated for other common sources, but, associated with high H2S and VOC emissions, a significant contribution to secondary aerosol production in a larger area is predictable. In effect, the significant levels of amines measured here would also be associated with the accumulation of pollutants that affect the entire Po Valley during Winter and Autumn (Masiol et al., 2015).

3.4 Correlation among amine concentrations and other atmospheric variables

Regarding the contribution that this method can offer in the study of atmospheric phenomena, in our preliminary study we observed that the amines contained in PM10 samples correlate rather strongly between themselves (Pearson's correlation coefficients are reported Table S9), indicating that their presence in PM is due to similar processes, i.e., the rapid acid–base reactions with atmospheric acids as described in previous studies (e.g., Ge et al., 2011a). The concentration of all amines correlates strongly or moderately with PM10 (r>0.55, except ethylamine r=0.38), as expected for the aerosol components associated with the secondary fraction (that is significant in the Po Valley). In effect, amines are also strongly correlated with nitrate (r>0.52) and ammonium (r>0.51), supporting the hypothesis that amines are present in particulate matter mainly as a result of acid–base processes that lead to the formation of sulfates and nitrates.

Regarding the sources of emission, it is worth noting that DMA (the amine present at higher concentrations) shows a strong correlation with potassium (r=0.73), supporting the hypothesis that biomass combustion processes are significant sources of amines. This hypothesis is further confirmed by the strong correlation (r=0.80) between DMA and OC (organic carbon concentration in PM10), taking into account that both OC and potassium in PM are closely associated with biomass burning emissions (Scotto et al., 2021; Masiol et al., 2020). However, OC could also be related to industrial emission sources, which then would also contribute to the emission of DMA. These strong correlations have not been found for some amines. For example, significantly lower correlations of EA with both DMA and PM10 were estimated, possibly due to a specific source of EA (for example, traffic combustions) that differs from those that characterize other amines (biomass combustion, tanneries). Of course, this aspect is of great interest and needs further investigation. In this connection, the acquisition of more complete datasets (Masiol et al., 2020) that could include both traffic and biomass combustion markers and the use of adequate source apportionment methodologies (positive matrix factorization, PMF) will provide more detailed results regarding the amine sources of this area.

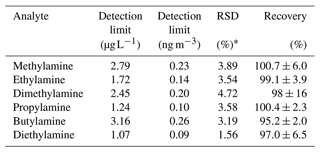

The PCA loading plot depicted in Fig. 2 shows that PC1, which describes 53.22 % of the total variance, is linked to the fine component of the atmospheric particulate, especially to the component of secondary origin, which includes all the amines. PC2, which expresses 14.98 % of the variance, appears to be more related to the coarse component of the particulate matter. The loading plot confirms the strong correlation between organic carbon, PM10, nitrate, and sulfate, as well as with different amines, in particular with DMA and MA. The graph also shows that the gaseous substances (NOx and NH3, i.e., the precursors of the secondary compounds) do not correlate at all with the secondary components of the particulate matter. This result indicates that the concentration of these pollutants does not significantly affect the local concentration or the composition of PM10 on a daily basis, which is influenced mainly by meteorological parameters and primary emission sources (Masiol et al., 2017).

The optimization of a fast sample preparation procedure followed by a UHPLC-FLD analysis allowed us to accurately determine the main alkylamines in the aerosol samples. The proposed analytical method performs well in terms of precision, detection limit, recoveries, and linear response range. The concentrations of amines measured in PM10 sampled in the tanning district (Chiampo Valley, Italy) are comparable to those quantified in other urbanized sites, possibly associated with the presence of important local emission sources, such as vehicular traffic, intense industrial activity, and biomass burning. These sources may have contributed, in particular, to the production of dimethylamine. Amine concentrations are strongly correlated with PM10 and with secondary inorganic ions, supporting the hypothesis that amines are present in particulate matter mainly as a result of acid–base processes that lead to the formation of nitrates and sulfates. Dimethylamine, which is the amine present at higher concentrations, shows strong correlations with both the organic component of PM10 and potassium, indicating the relevance of biomass combustion process emissions. We expect that the procedure developed here will find application in extensive environmental studies. In this connection, a promising perspective for the UHPLC-FLD method is the possibility to validate the analytical data obtained by the online aerosol analyzer (aerosol time-of-flight mass spectrometry, ATOF-MS; aerosol mass spectrometry, AMS) (Malloy et al., 2009; Bottenus et al., 2018; Huang et al., 2012; Giorio et al., 2015).

Complete datasets are reported in the Supplement. Details can be obtained upon request by contacting the authors.

The supplement related to this article is available online at: https://doi.org/10.5194/ar-1-29-2023-supplement.

DS and AT are the principal investigators; they are responsible for all research activities. LS supported the laboratory analysis of PM samples. GF coordinated the sampling campaigns and performed the OC/EC analysis. MR and SB were responsible for the LC-MS analysis. DB was involved in the statistical analysis of the results. FAM contributed to the interpretation of the data and to the text revision.

The contact author has declared that none of the authors has any competing interests.

Publisher’s note: Copernicus Publications remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims made in the text, published maps, institutional affiliations, or any other geographical representation in this paper. While Copernicus Publications makes every effort to include appropriate place names, the final responsibility lies with the authors.

We acknowledge the support from ARPA Veneto, Dept. of Vicenza (Italy), in the PM10 sampling campaign.

This paper was edited by Andreas Held and reviewed by two anonymous referees.

Akyüz, M.: Simultaneous determination of aliphatic and aromatic amines in ambient air and airborne particulate matters by gas chromatography-mass spectrometry, Atmos. Environ., 42, 3809–3819, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.atmosenv.2007.12.057, 2008.

Almeida, J., Schobesberger, S., Kürten, A., Ortega, I. K., Kupiainen-Määttä, O., Praplan, A. P., Adamov, A., Amorim, A., Bianchi, F., Breitenlechner, M., David, A., Dommen, J., Donahue, N. M., Downard, A., Dunne, E., Duplissy, J., Ehrhart, S., Flagan, R. C., Franchin, A., Guida, R., Hakala, J., Hansel, A., Heinritzi, M., Henschel, H., Jokinen, T., Junninen, H., Kajos, M., Kangasluoma, J., Keskinen, H., Kupc, A., Kurtén, T., Kvashin, A. N., Laaksonen, A., Lehtipalo, K., Leiminger, M., Leppä, J., Loukonen, V., Makhmutov, V., Mathot, S., McGrath, M. J., Nieminen, T., Olenius, T., Onnela, A., Petäjä, T., Riccobono, F., Riipinen, I., Rissanen, M., Rondo, L., Ruuskanen, T., Santos, F. D., Sarnela, N., Schallhart, S., Schnitzhofer, R., Seinfeld, J. H., Simon, M., Sipilä, M., Stozhkov, Y., Stratmann, F., Tomé, A., Tröstl, J., Tsagkogeorgas, G., Vaattovaara, P., Viisanen, Y., Virtanen, A., Vrtala, A., Wagner, P. E., Weingartner, E., Wex, H., Williamson, C., Wimmer, D., Ye, P., Yli-Juuti, T., Carslaw, K. S., Kulmala, M., Curtius, J., Baltensperger, U., Worsnop, D. R., Vehkamäki, H., and Kirkby, J.: Molecular understanding of sulphuric acid-amine particle nucleation in the atmosphere, Nature, 502, 359–363, https://doi.org/10.1038/nature12663, 2013.

ARPAV: Relazione Tecnica: I Monitoraggi della Qualità dell'Aria nell'Area della Concia Anno 2022, 1–54, https://www.arpa.veneto.it/arpav/chi-e-arpav/file-e-allegati/dap-vicenza/zona-concia/relazione-qualita-dellaria-zona-concia-2022.pdf (last access: 8 November 2023), 2023.

Backes, A., Aulinger, A., Bieser, J., Matthias, V., and Quante, M.: Ammonia emissions in Europe, part I: Development of a dynamical ammonia emission inventory, Atmos. Environ., 131, 55–66, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.atmosenv.2016.01.041, 2016.

Bai, J., Baker, S. M., Goodrich-Schneider, R. M., Montazeri, N., and Sarnoski, P. J.: Aroma Profile Characterization of Mahi-Mahi and Tuna for Determining Spoilage Using Purge and Trap Gas Chromatography-Mass Spectrometry, J. Food Sci., 84, 481–489, https://doi.org/10.1111/1750-3841.14478, 2019.

Bottenus, C. L. H., Massoli, P., Sueper, D., Canagaratna, M. R., VanderSchelden, G., Jobson, B. T., and VanReken, T. M.: Identification of amines in wintertime ambient particulate material using high resolution aerosol mass spectrometry, Atmos. Environ., 180, 173–183, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.atmosenv.2018.01.044, 2018.

Bzdek, B. R., Ridge, D. P., and Johnston, M. V.: Amine exchange into ammonium bisulfate and ammonium nitrate nuclei, Atmos. Chem. Phys., 10, 3495–3503, https://doi.org/10.5194/acp-10-3495-2010, 2010.

Chang, Y., Wang, H., Gao, Y., Jing, S., Lu, Y., Lou, S., Kuang, Y., Cheng, K., Ling, Q., Zhu, L., Tan, W., and Huang, R. J.: Nonagricultural Emissions Dominate Urban Atmospheric Amines as Revealed by Mobile Measurements, Geophys. Res. Lett., 49, e2021GL097640, https://doi.org/10.1029/2021GL097640, 2022.

Chen, Y., Lin, Q., Li, G., and An, T.: A new method of simultaneous determination of atmospheric amines in gaseous and particulate phases by gas chromatography-mass spectrometry, J. Environ. Sci., 114, 401–411, 2022.

Cheng, G., Hu, Y., Sun, M., Chen, Y., Chen, Y., Zong, C., Chen, J., and Ge, X.: Characteristics and potential source areas of aliphatic amines in PM2.5 in Yangzhou, China, Atmos. Pollut. Res., 11, 296–302, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apr.2019.11.002, 2020.

Choi, N. R., Lee, J. Y., Ahn, Y. G., and Kim, Y. P.: Determination of atmospheric amines at Seoul, South Korea via gas chromatography/tandem mass spectrometry, Chemosphere, 258, 127367, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chemosphere.2020.127367, 2020.

Denkenberger, K. A., Moffet, R. C., Holecek, J. C., Rebotier, T. P., and Prather, K. A.: Real-time, single-particle measurements of oligomers in aged ambient aerosol particles, Environ. Sci. Technol., 41, 5439–5446, https://doi.org/10.1021/es070329l, 2007.

Feng, H., Ye, X., Liu, Y., Wang, Z., Gao, T., Cheng, A., Wang, X., and Chen, J.: Simultaneous determination of nine atmospheric amines and six inorganic ions by non-suppressed ion chromatography using acetonitrile and 18-crown-6 as eluent additive, J. Chromatogr. A, 1624, 461234, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chroma.2020.461234, 2020.

Ge, X., Wexler, A. S., and Clegg, S. L.: Atmospheric amines – Part I. A review, Atmos. Environ., 45, 524–546, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.atmosenv.2010.10.012, 2011a.

Ge, X., Wexler, A. S., and Clegg, S. L.: Atmospheric amines – Part II. Thermodynamic properties and gas/particle partitioning, Atmos. Environ., 45, 561–577, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.atmosenv.2010.10.013, 2011b.

Giorio, C., Tapparo, A., Dallosto, M., Beddows, D. C. S., Esser-Gietl, J. K., Healy, R. M., and Harrison, R. M.: Local and regional components of aerosol in a heavily trafficked street canyon in central London derived from PMF and cluster analysis of single-particle ATOFMS spectra, Environ. Sci. Technol., 49, 3330–3340, https://doi.org/10.1021/es506249z, 2015.

Giorio, C., D'Aronco, S., Di Marco, V., Badocco, D., Battaglia, F., Soldà, L., Pastore, P., and Tapparo, A.: Emerging investigator series: aqueous-phase processing of atmospheric aerosol influences dissolution kinetics of metal ions in an urban background site in the Po Valley, Environ. Sci.-Proc. Imp., 24, 884–897, https://doi.org/10.1039/d2em00023g, 2022.

Huang, R.-J., Li, W.-B., Wang, Y.-R., Wang, Q. Y., Jia, W. T., Ho, K.-F., Cao, J. J., Wang, G. H., Chen, X., EI Haddad, I., Zhuang, Z. X., Wang, X. R., Prévôt, A. S. H., O'Dowd, C. D., and Hoffmann, T.: Determination of alkylamines in atmospheric aerosol particles: a comparison of gas chromatography–mass spectrometry and ion chromatography approaches, Atmos. Meas. Tech., 7, 2027–2035, https://doi.org/10.5194/amt-7-2027-2014, 2014.

Huang, Y., Chen, H., Wang, L., Yang, X., and Chen, J.: Single particle analysis of amines in ambient aerosol in Shanghai, Environ. Chem., 9, 202–210, https://doi.org/10.1071/EN11145, 2012.

Hubaux, A. and Vos, G.: Decision and Detection Limits for Linear Calibration Curves, Anal. Chem., 42, 849–855, https://doi.org/10.1021/ac60290a013, 1970.

Iqbal, M. A., Szulejko, J. E., and Kim, K. H.: Determination of methylamine, dimethylamine, and trimethylamine in air by high-performance liquid chromatography with derivatization using 9-fluorenylmethylchloroformate, Anal. Methods-UK, 6, 5697–5707, https://doi.org/10.1039/c4ay00740a, 2014.

JRC: Best Available Techniques (BAT) Reference Document for the Tanning of Hides and Skins, Report EUR 26130 EN, 290 pp., https://doi.org/10.2788/13548, 2013.

Khan, M. B., Masiol, M., Formenton, G., Di Gilio, A., de Gennaro, G., Agostinelli, C., and Pavoni, B.: Carbonaceous PM2.5 and secondary organic aerosol across the Veneto region (NE Italy), Sci. Total Environ., 542, 172–181, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2015.10.103, 2016.

Kieloaho, A. J., Hellén, H., Hakola, H., Manninen, H. E., Nieminen, T., Kulmala, M., and Pihlatie, M.: Gas-phase alkylamines in a boreal Scots pine forest air, Atmos. Environ., 80, 369–377, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.atmosenv.2013.08.019, 2013.

Lee, D. Y. and Wexler, A. S.: Atmospheric amines – Part III: Photochemistry and toxicity, Atmos. Environ., 71, 95–103, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.atmosenv.2013.01.058, 2013.

Liu, Z., Li, M., Wang, X., Liang, Y., Jiang, Y., Chen, J., Mu, J., Zhu, Y., Meng, H., Yang, L., Hou, K., Wang, Y., and Xue, L.: Large contributions of anthropogenic sources to amines in fine particles at a coastal area in northern China in winter, Sci. Total Environ., 839, 156281, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2022.156281, 2022.

Loukonen, V., Kurtén, T., Ortega, I. K., Vehkamäki, H., Pádua, A. A. H., Sellegri, K., and Kulmala, M.: Enhancing effect of dimethylamine in sulfuric acid nucleation in the presence of water – a computational study, Atmos. Chem. Phys., 10, 4961–4974, https://doi.org/10.5194/acp-10-4961-2010, 2010.

Lozanov, V., Petrov, S., and Mitev, V.: Simultaneous analysis of amino acid and biogenic polyamines by high-performance liquid chromatography after pre-column derivatization with N-(9-fluorenylmethoxycarbonyloxy)succinimide, J. Chromatogr. A, 1025, 201–208, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chroma.2003.10.094, 2004.

Majedi, S. M. and Lee, H. K.: Combined dispersive solid-phase extraction-dispersive liquid–liquid microextraction-derivatization for gas chromatography–mass spectrometric determination of aliphatic amines on atmospheric fine particles, J. Chromatogr. A, 1486, 86–95, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chroma.2016.06.079, 2017.

Malloy, Q. G. J., Li Qi, Warren, B., Cocker III, D. R., Erupe, M. E., and Silva, P. J.: Secondary organic aerosol formation from primary aliphatic amines with NO3 radical, Atmos. Chem. Phys., 9, 2051–2060, https://doi.org/10.5194/acp-9-2051-2009, 2009.

Masiol, M., Benetello, F., Harrison, R. M., Formenton, G., De Gaspari, F., and Pavoni, B.: Spatial, seasonal trends and transboundary transport of PM2.5 inorganic ions in the Veneto region (Northeastern Italy), Atmos. Environ., 117, 19–31, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.atmosenv.2015.06.044, 2015.

Masiol, M., Squizzato, S., Formenton, G., Harrison, R. M., and Agostinelli, C.: Air quality across a European hotspot: Spatial gradients, seasonality, diurnal cycles and trends in the Veneto region, NE Italy, Sci. Total Environ., 576, 210–224, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2016.10.042, 2017.

Masiol, M., Squizzato, S., Formenton, G., Khan, M. B., Hopke, P. K., Nenes, A., Pandis, S. N., Tositti, L., Benetello, F., Visin, F., and Pavoni, B.: Hybrid multiple-site mass closure and source apportionment of PM2.5 and aerosol acidity at major cities in the Po Valley, Sci. Total Environ., 704, 135287, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2019.135287, 2020.

Muthiya, S. J., Natrayan, L., Yuvaraj, L., Subramaniam, M., Dhanraj, J. A., and Mammo, W. D.: Development of Active CO2 Emission Control for Diesel Engine Exhaust Using Amine-Based Adsorption and Absorption Technique, Adsorpt. Sci. Technol., 2022, 8803585, https://doi.org/10.1155/2022/8803585, 2022.

Nielsen, C. J., D'Anna, B., Bossi, R., Bunkan, A. J. C., Dithmer, L., Glasius, M., Hallquist, M., Hansen, A. M. K., Lutz, A., Salo, K., Maguta, M. M., Nguyen, Q., Mikoviny, T., Müller, M., Skov, H., Sarrasin, E., Stenstrøm, Y., Tang, Y., Westerlund, J., and Wisthaler, A.: Atmospheric Degradation of Amines (ADA), Summary report from atmospheric chemistry studies of amines, nitrosamines, nitramines and amides, CLIMIT project no. 201604, ISBN 978-82-425-2358-7, https://www.nilu.com/wp-content/uploads/dnn/02-2011-mka-ADA-final-report.pdf (last access: 8 November 2023), 2012.

Parshintsev, J., Rönkkö, T., Helin, A., Hartonen, K., and Riekkola, M. L.: Determination of atmospheric amines by on-fiber derivatization solid-phase microextraction with 2,3,4,5,6-pentafluorobenzyl chloroformate and 9-fluorenylmethoxycarbonyl chloride, J. Chromatogr. A, 1376, 46–52, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chroma.2014.12.040, 2015.

Place, B. K., Quilty, A. T., Di Lorenzo, R. A., Ziegler, S. E., and VandenBoer, T. C.: Quantitation of 11 alkylamines in atmospheric samples: separating structural isomers by ion chromatography, Atmos. Meas. Tech., 10, 1061–1078, https://doi.org/10.5194/amt-10-1061-2017, 2017.

Płotka-Wasylka, J. M., Morrison, C., Biziuk, M., and Namieśnik, J.: Chemical Derivatization Processes Applied to Amine Determination in Samples of Different Matrix Composition, Chem. Rev., 115, 4693–4718, https://doi.org/10.1021/cr4006999, 2015.

Qiu, C., Wang, L., Lal, V., Khalizov, A. F., and Zhang, R.: Heterogeneous reactions of alkylamines with ammonium sulfate and ammonium bisulfate, Environ. Sci. Technol., 45, 4748–4755, https://doi.org/10.1021/es1043112, 2011.

Scotto, F., Bacco, D., Lasagni, S., Trentini, A., Poluzzi, V., and Vecchi, R.: A multi-year source apportionment of PM2.5 at multiple sites in the southern Po Valley (Italy), Atmos. Pollut. Res., 12, 101192, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apr.2021.101192, 2021.

Shen, W., Ren, L., Zhao, Y., Zhou, L., Dai, L., Ge, X., Kong, S., Yan, Q., Xu, H., Jiang, Y., He, J., Chen, M., and Yu, H.: C1-C2 alkyl aminiums in urban aerosols: Insights from ambient and fuel combustion emission measurements in the Yangtze River Delta region of China, Environ. Pollut., 230, 12–21, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envpol.2017.06.034, 2017.

Stanciulescu, M., Charland, J. P., and Kelly, J. F.: Effect of primary amine hydrocarbon chain length for the selective catalytic reduction of NOx from diesel engine exhaust, Fuel, 89, 2292–2298, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.fuel.2010.02.015, 2010.

Szulejko, J. E. and Kim, K. H.: A review of sampling and pretreatment techniques for the collection of airborne amines, TrAC-Trend. Anal. Chem., 57, 118–134, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.trac.2014.02.010, 2014.

Tang, X., Price, D., Praske, E., Lee, S. A., Shattuck, M. A., Purvis-Roberts, K., Silva, P. J., Asa-Awuku, A., and Cocker, D. R.: NO3 radical, OH radical and O3-initiated secondary aerosol formation from aliphatic amines, Atmos. Environ., 72, 105–112, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.atmosenv.2013.02.024, 2013.

Tzitzikalaki, E., Kalivitis, N., and Kanakidou, M.: Observations of gas-phase alkylamines at a coastal site in the east mediterranean atmosphere, Atmosphere-Basel, 12, 1454, https://doi.org/10.3390/atmos12111454, 2021.

VandenBoer, T. C., Markovic, M. Z., Petroff, A., Czar, M. F., Borduas, N., and Murphy, J. G.: Ion chromatographic separation and quantitation of alkyl methylamines and ethylamines in atmospheric gas and particulate matter using preconcentration and suppressed conductivity detection, J. Chromatogr. A, 1252, 74–83, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chroma.2012.06.062, 2012.

van Pinxteren, M., Fomba, K. W., van Pinxteren, D., Triesch, N., Hoffmann, E. H., Cree, C. H. L., Fitzsimons, M. F., von Tümpling, W., and Herrmann, H.: Aliphatic amines at the Cape Verde Atmospheric Observatory: Abundance, origins and sea-air fluxes, Atmos. Environ., 203, 183–195, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.atmosenv.2019.02.011, 2019.

Wang, Y., Yang, G., Lu, Y., Liu, Y., Chen, J., and Wang, L.: Detection of gaseous dimethylamine using vocus proton-transfer-reaction time-of-flight mass spectrometry, Atmos. Environ., 243, 117875, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.atmosenv.2020.117875, 2020.

Xiao, M., Hoyle, C. R., Dada, L., Stolzenburg, D., Kürten, A., Wang, M., Lamkaddam, H., Garmash, O., Mentler, B., Molteni, U., Baccarini, A., Simon, M., He, X.-C., Lehtipalo, K., Ahonen, L. R., Baalbaki, R., Bauer, P. S., Beck, L., Bell, D., Bianchi, F., Brilke, S., Chen, D., Chiu, R., Dias, A., Duplissy, J., Finkenzeller, H., Gordon, H., Hofbauer, V., Kim, C., Koenig, T. K., Lampilahti, J., Lee, C. P., Li, Z., Mai, H., Makhmutov, V., Manninen, H. E., Marten, R., Mathot, S., Mauldin, R. L., Nie, W., Onnela, A., Partoll, E., Petäjä, T., Pfeifer, J., Pospisilova, V., Quéléver, L. L. J., Rissanen, M., Schobesberger, S., Schuchmann, S., Stozhkov, Y., Tauber, C., Tham, Y. J., Tomé, A., Vazquez-Pufleau, M., Wagner, A. C., Wagner, R., Wang, Y., Weitz, L., Wimmer, D., Wu, Y., Yan, C., Ye, P., Ye, Q., Zha, Q., Zhou, X., Amorim, A., Carslaw, K., Curtius, J., Hansel, A., Volkamer, R., Winkler, P. M., Flagan, R. C., Kulmala, M., Worsnop, D. R., Kirkby, J., Donahue, N. M., Baltensperger, U., El Haddad, I., and Dommen, J.: The driving factors of new particle formation and growth in the polluted boundary layer, Atmos. Chem. Phys., 21, 14275–14291, https://doi.org/10.5194/acp-21-14275-2021, 2021.

Xie, H., Feng, L., Hu, Q., Zhu, Y., Gao, H., Gao, Y., and Yao, X.: Concentration and size distribution of water-extracted dimethylaminium and trimethylaminium in atmospheric particles during nine campaigns – Implications for sources, phase states and formation pathways, Sci. Total Environ., 631–632, 130–141, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2018.02.303, 2018.

Yao, L., Garmash, O., Bianchi, F., Zheng, J., Yan, C., Kontkanen, J., Junninen, H., Mazon, S. B., Ehn, M., Paasonen, P., Sipilä, M., Wang, M., Wang, X., Xiao, S., Chen, H., Lu, Y., Zhang, B., Wang, D., Fu, Q., Geng, F., Li, L., Wang, H., Qiao, L., Yang, X., Chen, J., Kerminen, V. M., Petäjä, T., Worsnop, D. R., Kulmala, M., and Wang, L.: Atmospheric new particle formation from sulfuric acid and amines in a Chinese megacity, Science, 361, 278–281, https://doi.org/10.1126/science.aao4839, 2018.

Zhou, S., Lin, J., Qin, X., Chen, Y., and Deng, C.: Determination of atmospheric alkylamines by ion chromatography using 18-crown-6 as mobile phase additive, J. Chromatogr. A, 1563, 154–161, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chroma.2018.05.074, 2018.