the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 License.

the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 License.

The evolution of carbon oxidation state during secondary organic aerosol formation from individual and mixed organic precursors

Yunqi Shao

Aristeidis Voliotis

Thomas J. Bannan

Jacqueline F. Hamilton

M. Rami Alfarra

Gordon McFiggans

This study reports the average carbon oxidation state () of secondary organic aerosol (SOA) particles formed through the photo-oxidation of o-cresol, α-pinene, isoprene and their mixtures – representative anthropogenic and biogenic precursors – in the Manchester Aerosol Chamber. Three independent mass spectrometric techniques, including two online instruments, namely a high-resolution time-of-flight Aerodyne aerosol mass spectrometer (HR-ToF-AMS) and a Filter Inlet for Gases and AEROsols coupled to an Iodide high-resolution time-of-flight chemical ionisation mass spectrometer (FIGAERO-CIMS), and one offline technique, namely ultra-high-performance liquid chromatography high-resolution mass spectrometry (UHPLC-HRMS), were employed to characterise the chemical composition of SOA and to derive average in mixtures of α-pinene–isoprene, o-cresol–isoprene, α-pinene–o-cresol and α-pinene–o-cresol–isoprene systems. This paper firstly reports the detailed analysis of particle average during SOA formation in mixed anthropogenic and biogenic systems using two online mass spectrometry techniques and one offline mass spectrometry technique simultaneously.

Across single-precursor experiments, generally declined with increasing SOA mass, suggesting a shift from highly oxygenated, low-volatility products at early stages towards more semi-volatile, less oxidised compounds at higher particle mass loading. This behaviour was robust across different initial precursor concentrations, implying that SOA growth is dominated by partitioning dynamics rather than initial precursors' reactivity.

Moreover, comparisons across analytical techniques demonstrate systematic differences, with FIGAERO-CIMS consistently reporting higher , UHPLC-HRMS (negative mode) aligning more closely with FIGAERO-CIMS, and HR-ToF-AMS underestimating due to its inability to resolve nitrogen-containing species.

Furthermore, correcting for the oxidation state of nitrogen () significantly reduced estimates in o-cresol experiments, likely reflecting the strong influence of CHON+ ion fragments.

Mixed-precursor experiments reveal that the isoprene suppressed the formation of highly oxygenated α-pinene products through OH scavenging and RO2 competition, lowering in mixed systems. In contrast, α-pinene–o-cresol mixtures showed elevated , likely contributed by the cross-interaction between precursor-driven RO2 forming multifunctional accretion products. The ternary mixture evolved to intermediate values between the single-precursor experiment, which could imply a balance between OH scavenging, RO2 competition and cross-interaction reaction.

- Article

(3387 KB) - Full-text XML

-

Supplement

(1015 KB) - BibTeX

- EndNote

The formation and evolution of secondary organic aerosol (SOA) from mixtures of volatile organic compounds (VOCs) play an important role in understanding ambient organic aerosol (OA) composition. While early chamber studies predominantly investigated SOA formation from individual precursors (Lee et al., 2011; Winterhalter et al., 2003; Pandis et al., 1991; Hoffmann et al., 1997; Eddingsaas et al., 2012; Kroll et al., 2005a; Ahlberg et al., 2017; Pullinen et al., 2020; Kroll et al., 2005b), more recent research has shifted towards exploring multi-precursor systems (Han et al., 2025; Chen et al., 2025; Cui et al., 2024), reflecting the chemical complexity of the real atmosphere, where anthropogenic and biogenic VOCs coexist and interact. These interactions can significantly alter SOA yields, volatility distributions and chemical composition, often through competition for oxidants or the formation of cross-products.

McFiggans et al. (2019) demonstrated that isoprene reduced SOA mass and yield by scavenging OH radicals and their derived products, thereby suppressing the formation of highly oxygenated molecules (HOMs) from α-pinene oxidation and increasing the overall volatility of the mixture. However, more recent findings by Voliotis et al. (2022a) showed that, although the addition of isoprene altered the chemical composition of the SOA and suppressed certain α-pinene-derived products, the overall volatility distribution remained largely unchanged, likely due to the formation of new products with comparable volatility distributions. Li et al. (2022) further demonstrated that isoprene can suppress SOA yields from anthropogenic aromatics (e.g. toluene, p-xylene) through OH scavenging, emphasising the importance of VOC competition. Additionally, Zhao et al. (2025) highlighted mechanistic interactions in mixed biogenic systems, showing that, in α-pinene and limonene mixtures, limonene-derived RO2 radicals and oxidation products facilitated the formation of cross-dimers, enhancing SOA yields. These findings highlighted the importance of the mechanistic interaction between the oxidation products of the precursor in understanding SOA formation in the presence of multiple VOCs.

Despite significant advances, the chemical characterisation of SOA from mixed-VOC systems remains challenging. OA in the ambient atmosphere comprises thousands of compounds, including hydrocarbons, alcohol, aldehydes and carboxylic acids, with a small fraction (∼ 10 %–30 %) of these being capable of being characterised at a molecular level by current techniques (Hoffmann et al., 2011). Moreover, the chemical complexity of OA increases if there are multiple OA sources (both anthropogenic and biogenic sources) that contribute to OA formation. A current lack of detailed chemical characterisation of these organic species makes it difficult to track the OA sources, understand their atmospheric processes and mitigate their adverse impacts. The majority of ambient SOA is generated by oxidation of VOCs with the dominant prevailing oxidants, hydroxyl radicals (OH), ozone (O3) and nitrate radicals (NO3), with their relative contributions varying throughout the day and night, leading to low-volatility products that partition into the particle phase (Atkinson et al., 2004). As SOA ages, its composition evolves through multi-generational oxidation (Kroll et al., 2005a; Ahlberg et al., 2017; Pullinen et al., 2020)

A useful framework to describe this chemical evolution is the average carbon oxidation state (), which increases with the extent of oxidation (Kroll et al., 2011). According to the valence rule, a simplified expression for the average of organic mixtures in terms of the molar oxygen-to-carbon (O C) and hydrogen-to-carbon (H C) ratios is shown in Eq. (1).

Changes in carbon oxidation state provide a valuable insight into the oxidation dynamics associated with the formation and evolution of ensemble SOA. For example, the generally increases by functionalisation, which can frequently occur in VOC oxidation, leading to C–O bonds, for example, replacing C–H or unsaturated C–C bonds. An exception to this is when functionalisation leads to the addition of nitro groups forming a C–N bond and remains the same. In contrast, the average remains unchanged by oligomerisation, which may occur after functionalisation and fragmentation reaction (Kroll et al., 2015). On the other hand, change in the average of particulate organic molecules is also associated with their volatility, which can strongly influence gas particle partitioning, resulting in changes in the ensemble chemical composition and increases in the OA mass concentration. In general, the overall volatility will decrease with more functionalised molecules and increase with fragmentation (Daumit et al., 2013). Changes in and atomic ratios (H C and O C ratios) upon SOA mass loading can therefore be useful tools in identifying the key process in the atmospheric ageing of SOA.

In our chamber studies of SOA formation in mixtures of α-pinene, isoprene and o-cresol, we have reported the chemical composition of SOA by means of offline ultra-high-performance liquid chromatography Orbitrap mass spectrometry (Voliotis et al., 2022b; Shao et al., 2022a). Oxidation products from the high-yield precursor, α-pinene, dominated SOA in its mixtures, whilst isoprene-derived compounds made a negligible contribution. Interactions in the oxidation of mixed precursors were found to lead to products uniquely found in the mixtures. In this study, we expand the investigation to report online measurements from the high-resolution time-of-flight Aerodyne aerosol mass spectrometers (HR-ToF-AMS) and Filter Inlet for Gases and AEROsols coupled to an Iodide high-resolution time-of-flight chemical ionisation mass spectrometer (FIGAERO-CIMS; Lee et al., 2014) to measure the near-real-time atomic ratios and to derive the oxidation state of SOA during these experiments. The HR-ToF-AMS technique has been widely used for analysing the non-refractory aerosol chemical composition (Aiken et al., 2008; Shilling et al., 2009; Presto et al., 2009; Chhabra et al., 2010; Docherty et al., 2018) and can provide sensitive and online measurements of SOA elemental composition. The FIGAERO-CIMS was used to provide measurements of both gas-phase and particle-phase chemical constituents of organic aerosols in real time. Both instruments have limitations precluding molecular identification (electron impact ionisation in the HR-ToF-AMS leads to extensive fragmentation, and the CIMS cannot resolve structural isomers or isobaric compounds; Lee et al., 2014). Nevertheless, both online instruments can provide the time profile of atomic ratios of the SOA and derived average carbon oxidation state to add the interpretation of the evolution of organic compounds to the offline measurement by ultra-high-performance liquid chromatography high-resolution mass spectrometry (UHPLC-HRMS).

The present study investigates the evolution of the average during SOA formation from single precursors and their mixture system, with a focus on linking the dynamics to underlying chemical mechanisms. Specifically, five key questions were addressed and examined in this study:

- i.

How does vary with SOA mass loading to provide insights into volatility and ageing processes?

- ii.

How do different initial precursor reactivities influence evolution in single-precursor experiments?

- iii.

How consistent are estimates across different analytical techniques and what does the respective bias imply?

- iv.

How do the nitrogen-containing compounds affect the estimation, particularly in systems that contain abundant CHON+ ion fragments?

- v.

How does the mixing of precursors impact the oxidation trajectories compared to the single-precursor system using as a diagnostic metric?

To answer these questions, a series of photochemical oxidation experiments were designed and conducted to produce SOA from the selected VOCs (α-pinene, isoprene and o-cresol) and their mixtures in the presence of neutral-seed particles (ammonium sulfate) and NOx. The experimental programme thereby included three single-precursor experiments, three binary precursor mixtures and one ternary mixture of precursors. For studying the effect of the initial VOC concentration on the particle composition and carbon oxidation state of SOA evolution, here, we also conduct single-precursor experiments at one-half and one-third of the initial concentration (and, hence, the reactivity in relation to the dominant oxidant in our experiments, the hydroxyl radical, OH). However, experiments with one-third of o-cresol reactivity and one-half of isoprene reactivity are not reported as a result of technical difficulties. The HR-ToF-AMS and FIGAERO-CIMS continuously sampled and measured the SOA particles throughout the experiment, and the entire chamber's contents were flushed through a filter for collection of the aerosol at the end of the experiment for subsequent offline analysis by UHPLC-HRMS.

2.1 Experimental procedure

The concept of iso-reactivity in relation to OH radicals was used to select the initial VOC concentrations in each experiment to enable comparable initial turnover of VOCs in the mixture with respect to OH radicals, such that the oxidation products from each VOCs would make comparable contributions at the chosen concentration and under the experimental conditions at the beginning of the experiment. The injected mass of VOC precursors was calculated based solely on their reactivity with OH radicals (Atkinson et al., 2004), excluding their consumption by other oxidants (e.g. O3). A total of 13 experimental conditions were planned, covering the α-pinene, isoprene and o-cresol single-precursor experiments (each at full, one-half and one-third reactivity, respectively); binary α-pinene–isoprene, α-pinene–o-cresol and o-cresol–isoprene mixtures; and their ternary mixture. Initial concentrations of each VOC in the binary and ternary mixtures were the same as the initial concentration in the one-half- and one-third-reactivity individual VOC experiments, respectively, ensuring comparable initial reactivity in relation to OH in all systems.

As described in Shao et al. (2022b), a “pre-experiment” programme and a “post-experiment” programme were conducted prior to and after each experiment. These two procedures consisted of multiple automatic fill–flush cycles with high flow rates (∼ 3 m3 min−1) and with purified air to condition and remove the unwanted contaminants in the chamber bag. A water condensation particle counter (WCPC; TSI 3786), O3 analyser, (Thermo Electron Corporation model 49C) and NO–NO2–NOx analyser (Thermo Electron Corporation model 42i) were used to monitor residual gas and particles in the chamber during the pre-experiment programme to ensure that their concentrations were close to zero in the bag prior to the chamber background procedure. The chamber background procedure was conducted for approximately 1 h, during which the chamber bag was kept in the dark, background data were collected, and all instrumentation remained stabile. An “experimental background” procedure was conducted in the next stage to establish the baseline contamination level in the chamber. This comprised continuous measurement after injecting VOC(s), NOx and seed particles sequentially and leaving the chamber to stabilise for an hour under dark conditions. All of the subsequent analyses presented in this work have the chamber background and experimental background subtracted. The baseline of the clean background and the experimental background were used to correct experimental data (See Sect. S1 in the Supplement). Actinometry and off-gassing experiments were performed regularly during our campaign to monitor the condition and cleanliness of the chamber bag.

The duration of each experiment was nominally 6 h after initial illumination under similar controlled environmental conditions (relative humidity or RH of 50 ± 5 % and temperature or T of 24 ± 2 °C). The average OH concentration during illumination was estimated from the decay rates of solely OH-reactive VOCs (e.g. o-cresol), yielding a concentration of approximately 1 × 106 mol cm−3. This OH source arose from O3 generated via NO2 photolysis, which was further photolysed in the moist chamber atmosphere. The summary of the initial conditions of the reported experiments is presented in Table 1 (noting the lack of one-third-reactivity o-cresol and one-half-reactivity isoprene owing to technical difficulties). To enhance confidence in the validity of our results and to address technical issues caused by occasional instrument failures, repeat experiments were conducted for selected single-precursor systems (both full and one-half reactivity), as well as for the binary- and ternary-mixture systems. However, this study presents results from only one experiment per system, with previous studies by Voliotis et al. (2021, 2022b) and Shao et al. (2022a) already demonstrating good agreement across repeated experiments in terms of maximum SOA mass, volatility distribution and chemical composition within each system. The particulate products were collected at the end of each experiment, flushing the entire chamber's contents through a pre-fired quartz filter (heating in a furnace at 550 °C for 5.5 h), which was subsequently wrapped in foil and refrigerated at −18 °C.

2.2 Instrumentation

2.2.1 Manchester Aerosol Chamber

All experiments were conducted in the Manchester Aerosol Chamber (MAC; Shao et al. (2022b). Briefly, the MAC operates as a batch reactor and consists of an 18 m3 volume Teflon FEP bag suspended by three rectangular extruded aluminium frames, housed in an air-conditioned enclosure. The enclosure is covered by reflective mylar material and is illuminated with two 6 kW Xenon arc lamps (XBO 6000 W/HSLA OFR, Osram) and a bank of halogen lamps (Solux 50 W/4700 K, Solux MR16, USA), with an intensity corresponding to the photolysis rate of NO2 (jNO2), around 1.83 × 10−3 s−1, throughout the entire experimental campaign. Conditioned air was introduced between the bag and the enclosure to maintain a constant chamber temperature throughout the experiment. Additionally, active water was used to cool the mounting bars of the halogen lamps and of the filter in front of the arc lamps to remove the unwanted heat from the lamps. Relative humidity (RH) and temperature (T) are controlled by the humidifier and the air conditioning that couple with the chamber. RH and T were continuously monitored by the dewpoint hygrometer and several thermocouples and resistance probes during the experiment. Liquid VOCs (α-pinene, isoprene and o-cresol; Sigma Aldrich, GC grade, ≥ 99.99 % purity) were introduced into the chamber through injection into a heated glass bulb for vaporisation and were subsequently flushed into the chamber with purified N2 (electronic-capture-device-grade nitrogen stream, ≥ 99.998 % purity). A custom-made cylinder (10 % ) containing NOx was used for NO2 injection into the MAC in ECD N2 as carrier gas. A Topaz model ATM 230 aerosol generator was used to produce ammonium sulfate seed particles by atomisation from ammonium sulfate solution (Puratonic, 99.999 % purity).

2.2.2 Online measurement

The NO–NO2–NOx and O3 analysers were used to measure the NO2 and O3 gas concentrations throughout the experiments. A semi-continuous gas chromatograph (6850 Agilent) coupled to a mass spectrometer (5975C Agilent; hereafter GC-MS) with a thermal desorption unit (Markes TT-24/7) was employed to monitor the time profile of VOC precursor decay. An Aerodyne high-resolution time-of-flight aerosol mass spectrometer (HR-ToF-AMS, Aerodyne Research Inc., USA) was used to measure organic mass loading and to characterise the composition of non-refractory organic particles. The HR-ToF-AMS instrument was calibrated by using monodisperse (350 nm) ammonium nitrate and ammonium sulfate particles prior to and after the experimental programme, referring to the standard protocol in Jayne et al. (2000) and Jimenez et al. (2003). The instrument operated in “V mode” during experiments and ran in mass spectra (MS) and particle time-of-flight (PToF) sub-modes for equal time periods (30 s in each section). The HR-ToF-AMS data were processed in Igor Pro 7.08 (Wavemeterics. Inc.) using the standard ToF-AMS analysis toolkit (version 1.21) for both unit mass resolution (UMR) and high-resolution (HR) analyses. The average ionisation efficiency of nitrate (IE = 9.38 × 108), the specific relative ionisation efficiencies (RIEs) for NH (3.57 ± 0.02) and SO (1.28 ± 0.01) from calibration, and the default RIE from Alfarra et al. (2004) of all organic compounds (RIE = 1.4) were all applied in the UMR and HR analysis. HR mass spectra were fitted using the method of DeCarlo et al. (2006) and analysed using the ToF-AMS analysis software that is reported on in Sueper et al. (2023). The ion-fitting process for high-resolution mass spectra in our analysis is based on the supporting information in Hildebrandt et al. (2011) since this is critical in the determination of the atomic ratio (O C) and (H C) of non-refractory organic material.

The operation of the time-of-fight chemical ionisation mass spectrometer with iodide ionisation coupled with a filter inlet for gases and aerosols (FIGAERO-CIMS; Lopez-Hilfiker et al., 2014) was described in Voliotis et al. (2021). Briefly, the particles were sampled for 30 min in the PTFE filter (Zefluor, 2.0 µm pore size) at 1 sL min−1, followed by a 33 min thermal desorption (15 min temperature ramp to 200 °C, 10 min holding time and 8 min cooling down to room temperature) with ultra-high purity N2 as the carrier gas. The instrument was run in negative-ion mode by producing an I− regent ion generated using a polonium-210 ionisation source to ionise methyl iodide (CH3I). The I− reagent ions enter the ion molecule reaction region (IMR) with N2 (ultra-high purity) as the carrier gas. An instrument background procedure for the particle-phase measurements was conducted in all of the experiments for subtraction from the measurements. The FIGAERO-CIMS data were processed by using the Tofware package in Igor Pro 7.0.8 (version 3.2.1., Wavemetrics ©) (Stark et al., 2015) for peak identification. A data set of assigned molecular formulae of the detected compounds was produced, allowing subsequent determination of the H C and O C ratios.

2.2.3 Offline measurement

Ultra-performance liquid chromatography ultra-high-resolution mass spectrometry (Dionex 3000, Orbitrap QExactive, Thermo Fisher Scientific) was employed for analysing the filter-sampled particulate. A detailed description of the instruments, experimental setup and data-processing methodology can be found in Shao et al. (2022a) and Pereira et al. (2021). Briefly, the preparation of the sample solution is as follows:

-

Filter samples were dissolved in 4 mL of LCMS-grade methanol, left to stand for 2 h at ambient temperature and then extracted using sonication for 30 min (Thermo Fisher Scientific FB15051).

-

A 0.22 µm pore size PDVF filter (Thermo Fisher Scientific) and a BD PlasticPak syringe (Thermo Fisher Scientific) were used for filtering the sample solution, followed by the addition of a further 1 mL of methanol onto the dry filter for the second extraction of samples with the same method.

-

The extracted solution was evaporated to dryness using a solvent evaporator (Biotage) under specified temperature (36 °C) and pressure (8 mbar) conditions. The evaporation step may result in the partial loss of the most volatile SOA components; however, most LCMS-detectable species are of low-volatility and thus are retained under these conditions.

-

The extract residual was re-dissolved in 1 mL solvent that consists of LCMS optimal-grade water and methanol in a ratio of 9 : 1.

Once the sample solutions were prepared, they were injected into the UHPLC-HRMS at 0.3 mL min−1, with 2 µL volume, by an autosampler held at 4 °C. The mass spectrometer was mass calibrated using ESI positive- and negative-ion calibration solutions (Pierce, Thermo Fisher Scientific) prior to sample analysis. The sample solution was passed through a reverse-phase C18 column (Accucore, Thermo Fisher Scientific) sized 100 mm long × 2.1 mm wide and with a 2.6 µm particle size, with temperature held at 40 °C. The mobile phase was composed of (A) LCMS optimal-grade water (Sigma Aldrich) and (B) methanol (LCMS optimal grade, Thermo Fisher Scientific) that both contain 0.1 % () formic acid (Sigma Aldrich, 99 % purity). The gradient elution started at 90 % (A) with a 1 min post-injection hold and then was decreased to 10 % (A) over 26 min, returned to the initial mobile phase at 28 min and ended with a 2 min re-equilibration In this instrument, electrospray ionisation (ESI, 35 eV) was performed for both positive and negative modes to charge the organic compounds in a range of 80 to 750. High-energy collisional dissociation from tandem mass spectrometry (MS2) was used to generate ion fragments for subsequent mass analyser detection. The resulting product ion spectra were then used to support structural characterisation and isomer identification of the compounds. Analysis of the extracted solvent (water : methanol = 9 : 1) and pre-conditioned bank filter was also performed with the same procedure as for subtraction from the measurements to ensure the exclusion of baseline noise and artefacts from sample preparation.

The data were processed by an automated methodology for non-targeted composition of small molecules (Pereira et al., 2021). This approach guided the peak identification and molecular formula assignment for detected compounds, enabling calculation of the signal-weighted , O C, H C and H C for each system.

2.3 Estimation of average carbon oxidation state ()

For compounds that contain only carbon, hydrogen and oxygen (designated “CHO” compounds), the average was straightforwardly determined using the atomic ratios O C and H C using Eq. (1), = 2 × O C-H C, in the analysis of data from all MS techniques.

For compounds that additionally contain nitrogen (“CHON” compounds), it is assumed that the nitrogen would exist as nitrate with = +5 if there are three or more oxygen atoms in the molecule and as nitrite with = +3 if there are fewer than three oxygen atoms. For CHON compounds, the is therefore calculated using Eq. (2), where the H, C, O and N are determined from the FIGAERO-CIMS and UHPLC-HRMS signal.

In the above, N C denotes the nitrogen-to-carbon ratios, = 3 if nO < 3, and = 5 if nO ≥ 3. The signal-weighted average determined by Eq. (2) will be presented in Sect. 3 and will be referred to as “accounting for ”. The HR-ToF-MS is unable to provide molecular information but provides the total particle ensemble C, H and O from the HR mass defect. However, retrieval of the mass defect with sufficient accuracy to attribute the N-containing compounds at the resolution of the instrument is too challenging to be considered to be robust. The calculated from HR-ToF-AMS data uses only C, H and O and uses Eq. (1) (i.e. implicitly not accounting for organic nitrogen in any CHON compounds present). For comparison with the HR-ToF-AMS-calculated , the average for CHON compounds measured by the FIGAERO-CIMS and UHPLC-HRMS technique has also been calculated ignoring the N and using Eq. (1), and this is referred to as “not accounting for ” in Sect. 3.

Strictly, the estimation of the average carbon oxidation state should account for the oxidation state of sulfur () in any sulfur-containing compounds (CHOS and CHONS compounds) in the particles. Given the challenges associated with the quantification of S-containing compounds in the FIGAERO-CIMS technique (Xu et al., 2016; D'Ambro et al., 2019), this study does not consider the contribution of in calculations. It was also shown by Du et al. (2022) that the influence of heteroatom S or NS on calculation would be negligible as a result of their low fractional abundance in the UHPLC-HRMS measurements (see also Shao et al. 2022a).

In this study, the average was reported based on a “representative experiment”, where only the compounds found in all replicate experiments can be confidently attributed to this particular system in both UHPLC-HRMS and FIGAERO-CIMS analyses. The HR-ToF-AMS measurements were selected from the same representative experiment as the UHPLC-HRMS and FIGAERO-CIMS analyses.

3.1 Average evolution of single-precursor experiments (with correction)

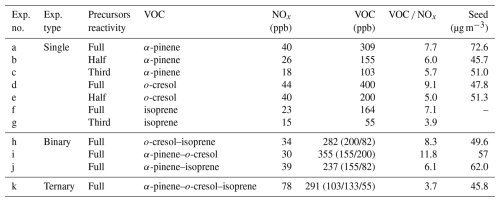

Figure 1 shows the average as a function of SOA mass concentration from single-α-pinene and single-o-cresol experiments with different initial reactivities derived from, respectively, FIGAERO-CIMS and UHPLC-HRMS measurements. All values shown here include the correction.

Figure 1Average (with correction) estimated from the FIGAERO-CIMS (lines) and UHPLC-HRMS (symbols; negative-ion mode denoted by stars, positive-ion mode denoted by squares) as a function of SOA mass. (a) Single-α-pinene experiments with three initial reactivities and (b) single-o-cresol experiments with two initial reactivities.

For the single-α-pinene system (Fig. 1a), the average estimated from FIGAERO-CIMS decreased with increasing SOA mass across all three reactivity levels. The magnitude of this decrease was similar among experiments. In the third reactivity experiment (lowest precursor concentration), the average declined from −0.24 to −0.46, while, in the one-half-reactivity experiment, it decreased from −0.31 to −0.51, and in the full-reactivity experiment, it decreased from −0.35 to −0.57.

The UHPLC-HRMS results in negative-ionisation mode show comparable trends. In negative-ionisation mode, the endpoint average values were −0.45 for the one-third-reactivity α-pinene experiment, which is higher than that of the one-half-reactivity ( = −0.61) and full-reactivity ( = −0.58) experiments. In positive-ionisation mode, the one-half- and full-reactivity experiments gave similar average magnitudes (around −0.95), which were about 0.26 higher than the one-third-reactivity experiment.

For the o-cresol system (Fig. 1b), the average from FIGAERO-CIMS decreased with increasing SOA mass in both reactivity experiments. In the full-reactivity experiment, the average declined from 0.12 to −0.26, while, in the one-half-reactivity experiment, it decreased from 0.09 to −0.37. At the very beginning of the one-half-reactivity experiment, the first point shows a lower of about −0.25, but this corresponds to exceptionally low SOA mass loadings.

The UHPLC-HRMS results show similar behaviour. In negative-ionisation mode, the full- and one-half-reactivity experiments gave comparable endpoint values of around −0.55. In positive-ionisation mode, however, the one-half-reactivity experiment has a higher (−0.48) than the full-reactivity experiment (−0.66).

3.2 Average evolution of single-precursor experiments (without correction)

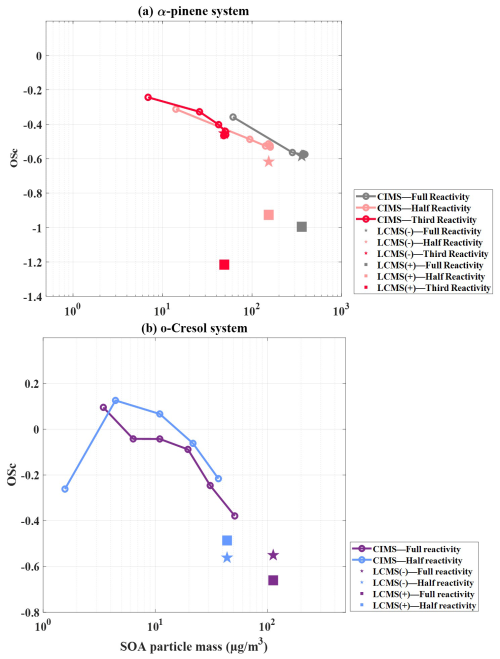

Figure 2 shows the evolution of as a function of SOA mass in single-α-pinene and single-o-cresol experiments across different reactivities, estimated using HR-ToF-AMS, FIGAERO-CIMS and UHPLC-HRMS measurements. It is important to note that the average values in Fig. 2 do not include the correction term.

Figure 2Average (without correction) as a function of SOA particle mass for single-precursor systems: (a) α-pinene with three initial reactivities and (b) o-cresol with two initial reactivities, obtained from HR-ToF-AMS (dots), FIGAERO-CIMS (lines) and UHPLC-HRMS (symbols; negative-ion mode denoted by stars, positive-ion mode denoted by squares).

In the single-α-pinene experiments (Fig. 2a), the HR-ToF-AMS is able to estimate at a lower particle mass during the rapid early growth phase compared with the other two techniques. The one-half-reactivity experiment exhibits the highest average (−1 to −0.5), followed by the by the full-reactivity experiment (: −1.6 to −0.7), while the one-third-reactivity experiment remains the lowest (: −2.48 to −0.68). In both the full- and one-half-reactivity experiments, the average initially increases and then declines as SOA mass builds, whereas, in the one-third-reactivity experiment, it increases continuously until the end of the experiment. By contrast, FIGAERO-CIMS consistently reports higher than the AMS across all three experiments. For FIGAERO-CIMS, the full- (: −0.17 to −0.40) and one-half-reactivity (: −0.17 to −0.32) experiments give comparable values, with both being slightly lower than the one-third-reactivity experiment (: −0.07 to −0.22), which is the opposite trend to that observed with AMS measurement. The UHPLC-HRMS results also align more closely with FIGAERO-CIMS, with the one-third-reactivity experiment giving of −0.34 in negative-ionisation mode and −0.19 in positive-ionisation mode, with the negative-ionisation values all being comparable to the FIGAERO-CIMS estimates.

For the single-o-cresol experiments, the HR-ToF-AMS-derived average shows a broadly increasing trend with SOA mass under both full- and one-half-reactivity conditions, with magnitudes ranging from −1.2 to 0.2 (Fig. 2b). The two experiments are generally comparable, except for the fact that the full-reactivity experiment exhibits a slight decline in average once SOA mass peaks at ∼ 10 µg m−3. In addition, FIGAERO-CIMS estimation showed higher average than HR-ToF-AMS measurements, with comparable values between the two reactivity conditions and a clear decrease from ∼ 0.4 to ∼ 0 as particle mass increases. The UHPLC-HRMS measurements also show similar behaviour across reactivities. In negative-ionisation mode, the average is ∼ 0.14 in both experiments, while, in positive mode, the full-reactivity experiment gives −0.36, about 0.11 lower than the one-half-reactivity experiment.

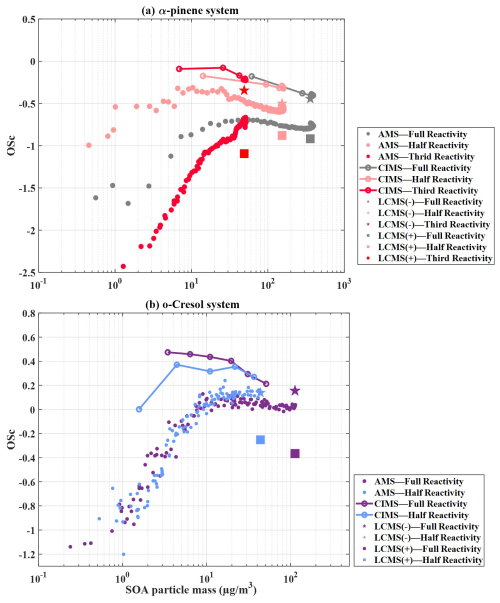

3.3 Average evolution in mixed-precursor systems (with correction)

Figure 3 illustrates the average evolution as a function of SOA mass concentration from mixed-precursor systems, along with their reference single experiments, as obtained from FIGAERO-CIMS and UHPLC-HRMS measurements. All values shown here include the correction.

Figure 3Evolution of the average (with correction) as a function of SOA mass concentration for binary and ternary precursor systems compared with the corresponding single-precursor reference experiments. Results are shown for FIGAERO-CIMS (lines) and UHPLC-HRMS (symbols; negative-ion mode denoted by stars, positive-ion mode denoted by squares). Panels show (a) α-pinene–isoprene mixture, (b) o-cresol–isoprene mixture, (c) α-pinene–o-cresol mixture and (d) ternary α-pinene–o-cresol–isoprene system.

3.3.1 α-pinene–isoprene binary system

Figure 3a shows that the average in the one-half-reactivity α-pinene experiment exhibits a declining trend (−0.31 to −0.51) similar to that observed in the α-pinene–isoprene binary mixture (: −0.42 to −0.65) based on FIGAERO-CIMS measurements. For comparison, we also include the single full-reactivity isoprene experiment as a reference, noting that the single one-half-reactivity isoprene experiments were not available. In the single-isoprene experiment, SOA mass concentrations were negligible (< 1 µg m−3, close to chamber background), while the corresponding average remained between −0.2 and 0.4.

The UHPLC-HRMS results demonstrated comparable average in negative-ionisation mode between the binary mixture and the single-α-pinene experiment (and align with the FIGAERO-CIMS endpoints at ). In positive-ionisation mode, however, the single full-reactivity α-pinene experiment shows a slightly higher than the mixture () (Fig. 3a).

3.3.2 o-cresol–isoprene binary system

From FIGAERO-CIMS measurements, both the binary o-cresol–isoprene and the single-o-cresol experiment display a decrease in average with increasing SOA mass beyond ∼ 3 µg m−3, as shown in Fig. 3b. In the binary-mixture system, the average declines from 0.38 at 3 µg m−3 to −0.21 by the end of the experiment. For the single-o-cresol run, the average starts around −0.25 during the initial low-mass period (< 3 µg m−3, roughly the first hour) and then decreases more modestly from 0.12 to −0.26 as SOA mass increases (Fig. 3b). For reference, results from single-isoprene experiments are also shown in Fig. 3b. However, the SOA mass concentrations were close to the chamber background, and so their average estimates should be interpreted with caution.

In the UHPLC-HRMS measurements, the positive-ionisation mode has comparable average values for the binary-mixture and single-o-cresol systems (). In contrast, the negative-ionisation mode shows slightly higher average in the single-o-cresol experiment () than in the binary mixture () (Fig. 3b).

3.3.3 o-cresol–α-pinene binary system

Figure 3c shows that the FIGAERO-CIMS average decreases with SOA mass concentration above ∼ 3 µg m−3 in the binary o-cresol–α-pinene system, as well as in the single one-half-reactivity o-cresol and α-pinene experiments. In the binary-mixture system, the average declines from 0.09 to −0.34, a change comparable to that observed in the single one-half-reactivity o-cresol experiment (0.12 to −0.26) but larger than that in the single one-half-reactivity α-pinene experiment (−0.31 to −0.51).

In the negative-ionisation mode of UHPLC-HRMS measurements, the binary mixture has an average of −0.63, in reasonable agreement with the single one-half-reactivity α-pinene experiment. By contrast, in positive-ionisation mode, the binary mixture produces a substantially lower average () than either of the single-precursor experiments, which were for o-cresol and for α-pinene.

3.3.4 α-pinene–isoprene–o-cresol ternary system

Figure 3d shows that the average exhibits a declining trend with increasing SOA mass in the ternary-mixture system, as well as in all single-precursor experiments. In the ternary-mixture system, the FIGAERO-CIMS average decreases from −0.16 to −0.35, falling between the single one-third-reactivity α-pinene experiment (: −0.24 to −0.26) and the one-half-reactivity o-cresol experiment (: 0.10 to −0.21, excluding the first hour when SOA mass was very low). This suggests contributions from both precursors. It is worth noting that data for the one-third-reactivity o-cresol experiment were not available due to instrument failure. For isoprene, the single one-third-reactivity experiment produced only ∼ 2 µg m−3 of measurable SOA mass. In this case, the average estimated by FIGAERO-CIMS decreased sharply from ∼ 1 to −0.5.

The UHPLC-HRMS results show that, in negative-ionisation mode, the ternary-mixture system has an average comparable to that of the single one-half-reactivity o-cresol experiment () but slightly lower than that of the single one-third-reactivity α-pinene experiment (). By contrast, in positive-ionisation mode, the ternary mixture has an average similar to that of the single one-third-reactivity α-pinene experiment () but much lower than that of the single one-half-reactivity o-cresol experiment ().

4.1 Average evolution with SOA mass and implication for volatility and SOA ageing

The evolution of average that was estimated accounting for the term as a function of SOA mass could provide insight into the underlying chemical processes of SOA formation and ageing. In the single-α-pinene and single-o-cresol experiments across all initial reactivities (Fig. 1), estimated from FIGAERO-CIMS measurements generally shows a declining trend as SOA mass increases. This behaviour suggested an increasing contribution from less oxidised material as particulate matter loading builds. It is possible that SOA growth is dominated by highly oxygenated, low-volatility products, likely formed via functionalisation of the precursor at the early stage. As SOA mass accumulates, the absorptive capacity of the particles increases, allowing semi-volatile, less oxidised compounds to partition, thereby driving down the bulk average . This interpretation is supported by the companion study of Voliotis et al. (2021), which reported pronounced fragmentation and a higher fraction of more volatile products in the single-α-pinene system, that such species could contribute at later stages once sufficient mass had accumulated.

Importantly, this relationship between average and SOA mass is consistent across different initial precursor concentrations. In the single-α-pinene experiments, all three reactivity levels (full, one-half, one-third) follow the same qualitative decline, showing that the observed behaviour is robust in relation to the starting conditions. For single-o-cresol experiments, the one-half-reactivity experiment begins with lower average than the full-reactivity experiment, but once the SOA mass reaches a comparable level, the two converge and decline together. This demonstrates that average evolution is primarily controlled by the partitioning balance during particle growth rather than the absolute precursor concentration.

The estimated average values from UHPLC-HRMS (accounting for the term) across the three α-pinene experiments show small differences, but the in negative-ionisation mode is consistently higher than in positive-ionisation mode. A plausible explanation is that the negative-ionisation mode preferentially detects deprotonated acids and highly oxygenated compounds (e.g. carboxylic acids), whereas the positive-ionisation mode favours compounds with readily protonated functional groups, which are typically less acidic and less oxidised species. The negative-ionisation-mode also aligns closely with the FIGAERO-CIMS endpoint values, likely because both techniques are more sensitive to highly oxygenated, low-volatility species and therefore capture a similar subset of the SOA composition. For the single-o-cresol system, the average values in negative-ionisation mode are comparable between the full- and one-half-reactivity experiments. This similarity is mainly contributed by nitro-aromatic molecules, which are dominant products in o-cresol oxidation and are sensitively detected in negative-ionisation mode (Shao et al; 2022a). On the other hand, the positive-ionisation-mode average in the one-half-reactivity experiment is higher than that of the full-reactivity experiment, suggesting that the latter may contain a larger fraction of less-oxidised neutral species and oligomeric condensation products.

4.2 Influence of precursor mixture on average during SOA formation

While the metric in single-volatile-precursor systems has been considered, its application to SOA formed from mixtures of VOCs remains limited. Yet, in the real atmosphere, SOA almost always derives from multiple precursors undergoing simultaneous reactions. Examining how mixtures alter trends compared with single-precursor experiments could offer novel insights into whether additional or modified chemical processes emerge when different VOCs react simultaneously. Beyond identifying these mechanistic differences, such comparisons provide useful constraints for future modelling efforts that aim to represent the chemical complexity of ambient SOA. To support this evaluation, this study presents the trend of average values (accounting for the × N C correction term) driven by FIGAERO-CIMS and UHPLC-HRMS, shown as a function of increasing SOA particle mass in binary- and ternary-mixture precursor mixture systems and compared against the corresponding single-precursor reference experiments. Corresponding O : C, H : C and N : C ratios for each mixture system are shown in Sect. S2 (Figs. S2–S5) to provide additional details underlying the average evolution.

4.2.1 α-pinene–isoprene binary system

According to FIGAERO-CIMS measurement, both the α-pinene–isoprene mixture system and the single one-half-reactivity α-pinene experiment show decreasing average with increasing SOA mass (Fig. 3a). However, the binary system is consistently offset to slightly lower at comparable mass loadings, likely reflecting suppression of highly oxygenated α-pinene products by isoprene (via RO2 competition and reduced HOM formation) and a larger relative contribution of less oxidised condensable molecules as the aerosol grows. Isoprene oxidation with OH radicals primarily produces semi-volatile C4–C5 species with high volatility (e.g. hydroxycarbonyls), which could suppress α-pinene SOA yields in mixed systems (Wennberg et al., 2018; Stroud et al., 2001; Carlton et al., 2009). An alternative interpretation is that these semi-volatile isoprene products partition onto the growing α-pinene-driven particle phase, lowering the average of the mixture. This interpretation is consistent with the findings of Voliotis et al. (2022a), where isoprene-driven products accounted for ∼ 3 % of the total FIGAERO-CIMS signal in the binary system. Moreover, comparison across experiments indicates higher N C ratios in the binary system than in the single one-half-reactivity α-pinene experiment (see Fig. S2c), suggesting that the presence of isoprene enhances the contribution of CHON+ ion fragments, which further drives down the average in the mixed system.

The UHPLC-HRMS results agree fairly with these trends (Fig.3a). In negative-ionisation mode, the mixed system has a slightly higher average than the single one-half-reactivity α-pinene experiment, likely reflecting additional condensable acidic or highly oxygenated products from isoprene that are preferentially detected in negative-ionisation mode. By contrast, in positive-ionisation mode, the binary system shows a slightly lower average than the single one-half-reactivity α-pinene experiment, which suggested that the partitioning balance might shift towards less oxidised semi-volatile or oligomeric species when isoprene is present.

4.2.2 o-cresol–isoprene binary system

The binary o-cresol–isoprene system shows an average evolution that can be described in two stages based on the FIGAERO-CIMS data. At the beginning of the experiment, when SOA mass was exceptionally low in both the binary and the single one-half-reactivity o-cresol system, the mixture exhibits a substantially higher average (Fig. 3b). This might suggest the formation of highly oxygenated accretion products when isoprene is present. Such HOM-like species may arise from RO2 cross-reactions between isoprene and o-cresol-driven radicals, as well as from nitroaromatic compounds formed under NOx conditions. Although these species likely represent only a small fraction of the particle mass, their high oxygen content can disproportionately elevate the average in the early stage of experiments.

The average declines as SOA mass increases, likely reflecting the fact that isoprene acts as an OH scavenger in the binary-mixture system. This reduces the OH available for o-cresol oxidation and suppresses the formation of highly oxidised o-cresol products. Generally, o-cresol RO2 radicals generated via OH addition undergo autoxidation to form HOMs, but, in the mixture, these pathways are potentially curtailed by competition with isoprene-driven RO2 and NOx. Instead of HOM formation, the chemistry is likely diverted towards accretion or fragmentation channels, producing less oxidised products. This shift could reduce the contribution of highly oxygenated o-cresol products, explaining why the binary-mixture system evolves towards lower average than the single one-half-reactivity o-cresol experiment at a higher SOA mass.

In the UHPLC-HRMS measurements, the positive-ionisation mode has comparable average values for both the single one-half-reactivity o-cresol and the binary o-cresol–isoprene experiments (Fig. 3b), suggesting that both systems may generate a similar contribution of less acidic or neutral compounds. In contrast, the negative-ionisation mode has higher average in the single one-half-reactivity o-cresol experiment compared with the binary-mixture system. This likely reflects a relatively lower contribution of CHON compounds in the single one-half-reactivity o-cresol experiment compared to in the mixture system as the negative-ionisation mode is particularly sensitive to nitroaromatic species that dominate the CHON class. These nitrogen-containing oxygenated compounds could affect the correction term, leading to lower average values when they are abundant. Previous work has shown that CHON compounds dominate o-cresol SOA (> 95 % of the signal in both single and binary systems; Shao et al., 2022a), even though those results were obtained under full-reactivity conditions. This observation still highlights the influence of CHON species in average estimation and reminds us of the importance of SOA chemical composition, as well as of the compound classes to which each instrument is most sensitive.

4.2.3 α-pinene–o-cresol binary system

The average that is estimated from FIGAERO-CIMS measurements in the α-pinene–o-cresol binary system decreases with increasing SOA mass concentration. At the early stage, the mixture exhibits average values that are comparable to the single one-half-reactivity o-cresol experiment but that are consistently higher than the single one-half-reactivity α-pinene experiment with overlapping SOA mass (Fig. 3c). One possible explanation is that FIGAERO-CIMS has a high sensitivity to nitroaromatic products generated from o-cresol oxidation (Voliotis et al., 2021), and so the binary-mixture system is weighted towards these highly oxygenated aromatic products. This sensitivity likely explains why the binary-mixture system shows a similar magnitude of average in relation to the single one-half-reactivity o-cresol experiment despite α-pinene being the higher SOA yield precursor. Towards the end of the experiment, the SOA mass of the binary mixture approaches that of the single one-half- reactivity α-pinene experiment, but its average remains higher, which might be attributed to the formation of additional multifunctional, low-volatility products via cross-reactions between α-pinene- and o-cresol-driven RO2 radicals.

Interestingly, this behaviour is not as consistent as in the o-cresol–isoprene binary system, where the mixture evolved towards lower average values than the single-precursor experiment by the end of the experiment. The difference can be explained by the fact that isoprene-driven RO2 (highly volatile) suppresses the formation of highly oxygenated o-cresol products, lowering the average as the SOA mass increases. On the other hand, α-pinene-driven semi-volatile RO2 favours the formation of multifunctional oxygenated accretion products that elevate the average of the binary-mixture system. Moreover, α-pinene does not act as a strong OH scavenger compared with isoprene according to their reactivity (Dillon et al., 2017), and so o-cresol oxidation by OH might be partly retained, and autoxidation of o-cresol-driven RO2 may still proceed to form low-volatility oxygenated dimers.

The binary-mixture system shows a slightly lower average than the single o-cresol experiment in negative-ionisation mode of UHPLC-HRMS measurements (Fig. 3c). From the accompanying atomic ratios (see Fig. S4), this is driven by lower O : C and higher H : C ratios in the mixed precursor system, while N C is comparable or smaller, which could explain the fact that the difference is not due to a larger nitrogen-containing compound correction. In contrast, the average in the binary mixture is substantially lower than in either single-precursor experiment in positive-ionisation mode (Fig. 3c). This likely reflects a greater contribution of less acidic, lower O C neutral species and oligomers produced through cross-interactions in the binary-mixture system compared to both single-precursor experiments, which are preferentially detected in positive-ionisation mode.

4.2.4 Ternary system

The average in the ternary α-pinene–o-cresol–isoprene system decreases as SOA mass builds up (Fig. 3d) based on FIGAERO-CIMS measurements. Within the overlapping SOA mass range, the mixture sits between the single one-third-reactivity α-pinene and the single one-half-reactivity o-cresol experiments, with average values that are higher than those of the α-pinene experiment and lower than those of the o-cresol experiment. This behaviour may suggest that several competing chemical processes are involved in the ternary-mixture system rather than one dominant mechanism. For example, isoprene can act as an OH scavenger, slowing the multi-generational oxidation of α-pinene and o-cresol and thereby suppressing the formation of highly oxygenated products. The presence of isoprene may also enhance the RO2+NO reaction, diverting chemistry towards organonitrates and fragmentation products while limiting RO2 + HO2 pathways that typically drive functionalisation and higher average . Also, cross-interactions between o-cresol-driven RO2 and α-pinene- or isoprene-driven RO2 could further suppress autoxidation of o-cresol precursors, with consequences for both O C and N C atomic ratios. Together, these effects may explain why the ternary system evolves to intermediate values, but the relative importance of each pathway remains unclear.

The UHPLC-HRMS negative-ionisation mode reported that the average in the ternary-mixture system is comparable to the single one-half-reactivity o-cresol experiment but slightly lower than the single one-third-reactivity α-pinene system (Fig. 3d). This suggests that nitroaromatic and other highly oxygenated CHON species, mainly characteristic of o-cresol oxidation, remain an important contribution within the mixture system. In contrast, the positive-ionisation mode indicates that the ternary-mixture system aligns more closely with the single-α-pinene experiment. This points to a strong influence of neutral and oligomeric products in the ternary-mixture system, likely including accretion products formed through cross-interactions between precursors.

4.3 Average comparison across three mass spectrometry techniques

Although is widely used as a metric to characterise SOA, its estimation depends strongly on the measurement technique. In this study, we showed a comparison across HR-ToF-AMS, FIGAERO-CIMS and UHPLC-HRMS to illustrate how instrumental properties impact the estimation of SOA particles. The combination of online and offline mass spectrometric techniques to estimate average has not been widely adopted, particularly in mixed-precursor chamber studies.

As seen in Fig. 2, the FIGAERO-CIMS reported a higher estimated average (not accounting for ) compared to the UHPLC-HRMS and HR-ToF-AMS values in α-pinene and o-cresol experiments across all initial reactivities, likely due to its strong sensitivity towards highly oxygenated (Lee et al., 2014), low-volatility compounds and the potential contribution of thermal decomposition fragments (Du et al., 2022). Moreover, the averaged values in the UHPLC-HRMS negative-ionisation mode broadly agree with the FIGAERO-CIMS endpoint values, which might reflect their shared bias towards acidic and highly oxygenated compounds, whereas the positive-ionisation mode favours the detection of the less oxidised neutral or oligomeric species, leading to lower average values. The HR-ToF-AMS shows an average estimation that is generally lower than that of FIGAERO-CIMS but higher than that of the positive-ionisation mode of UHPLC-HRMS (Fig. 2). For single-α-pinene experiments, HR-ToF- AMS shows a similar decline trend as the FIGAERO-CIMS in terms of average in the full- and one-half-reactivity experiments but diverges in the one-third-reactivity experiment, while, for o-cresol, the HR-ToF-AMS reports an initial rise and then a plateau. These discrepancies likely arise due to the HR-ToF-AMS being unable to unambiguously resolve nitrogen-containing species, and so contributions from CHON+ and CHONS ion fragments are either missed or misclassified as CHO fragments. This limitation biases the elemental ratios, particularly lowering O C and therefore depressing the calculated . Unlike the HR-ToF-AMS, the calculation of average in FIGAERO-CIMS and UHPLC-HRMS measurements is still based on well-identified CHON compounds. This structural limitation suggested that HR-ToF-AMS-estimated values are not directly comparable to those of FIGAERO-CIMS and/or UHPLC-HRMS, even when all are shown in the form of “not accounting for ”. The issue is especially relevant for excessive aromatic and nitrate SOA, where organonitrate species (CHON, CHONS) are abundant in chamber experiments with NOx and ammonium sulfate (Surratt et al., 2007, 2008; Bruns et al., 2010; Fry et al., 2009). In such cases, the true should be calculated as 2O C − H C − xN C − yS C (Kroll et al., 2011). While the contribution of sulfur-containing groups is typically small, the nitrogen effect is substantial in average calculations.

Moreover, neutral losses can occur in the HR-ToF-AMS during thermal desorption as some thermally labile or highly volatile compounds can desorb as neutral fragments (e.g. CO2 or H2O). This can also lead to an underestimation of certain oxygenated or heteroatom-containing species, biasing the measured elemental ratios (e.g. O : C and N : C) and adding uncertainty to the calculated average .

4.4 Effect of accounting on average estimation in single-precursor system

This section evaluates the influence of the nitrogen correction term on the estimated in single-α-pinene and single-o-cresol experiments using FIGAERO-CIMS and UHPLC-HRMS measurements.

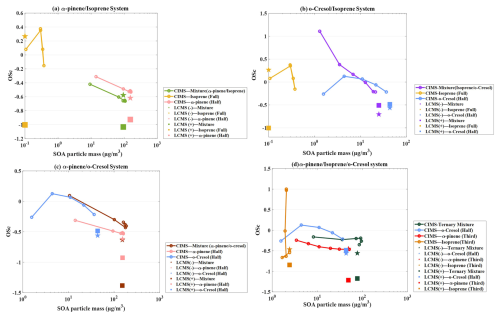

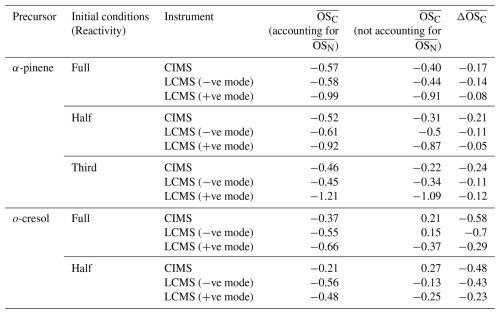

Table 2Average for single-α-pinene and single-o-cresol experiments across all reactivities, estimated from FIGAERO-CIMS (hereafter CIMS) and UHPLC-HRMS (hereafter, LCMS) measurements. For FIGAERO-CIMS, values correspond to the endpoint of each experiment, while UHPLC-HRMS values are based on filter extracts collected at the experiment endpoint. was estimated both accounting for and not accounting for the term of and the difference, (accounting for and not accounting for ).

As noted earlier, accounting for can have a non-negligible effect on the estimation of average of bulk SOA. Table 2 summarises the average of single-α-pinene and single-o-cresol experiments across all reactivities as estimated from FIGAERO-CIMS and UHPLC-HRMS measurements. It is reported that ignoring the term generally biases the estimation of average upward, leading to consistently higher average values across both instruments (all ).

In the single-α-pinene experiments, the downward adjustment associated with including the nitrogen correction term ( × N C) is fairly consistent across FIGAERO-CIMS and UHPLC-HRMS measurements ( ≈ −0.05 to −0.2), which might suggest relatively small contributions of N-containing products at the endpoints. By contrast, the corrections are much larger in the single-o-cresol experiments, particularly in the UHPLC-HRMS negative-ionisation mode ( ≈ −0.43 to −0.70) and FIGAERO-CIMS measurements ( ≈ ∼ 0.5), with moderate values in the UHPLC-HRMS positive-ionisation mode ( ≈ −0.23 to −0.29). The larger adjustment in o-cresol experiments likely arises from the fact that its oxidation is dominated by nitroaromatic oxygenated compounds. These nitrogen-containing species are particularly well captured in the negative-ion mode of UHPLC-HRMS (and also by CIMS), and, because of their abundance, they contribute a strong influence on the ⋅ N C correction term. As a result, their dominance drives a pronounced reduction in the estimated average .

It is important to note that, for FIGAERO-CIMS and UHPLC-HRMS, including or excluding the correction term in the average calculation is a deliberate choice, and its impact depends strongly on the identified chemical composition of the SOA. By contrast, the HR-ToF-AMS cannot resolve nitrogen-containing products, which leads to a systematic misclassification of CHON species as CHO fragments. This structural limitation, as discussed in Sect. 4.3, highlights the need for caution when interpreting AMS-derived values as the inability to account for can bias comparisons with FIGAERO-CIMS and UHPLC-HRMS measurements.

This study reframes the interpretation of SOA chemistry by using average as a diagnostic tool to explore the evolution of SOA from both single- and mixed-precursor systems. Rather than focusing on detailed product identification, which has been addressed in our previous work, we emphasise how trends provide broader insights into volatility, ageing pathways and precursor interactions.

We reported that average generally declines as SOA mass increases in all mixed-precursor systems, consistently with an increasing role of semi-volatile and less oxidised species at higher loadings from FIGAERO-CIMS measurements (accounting for correction). This behaviour highlights the role of as a proxy for functionalisation versus fragmentation pathways and SOA volatility.

Another finding of this study is that the inclusion of the correction substantially reduces average estimates, particularly in o-cresol experiments, which are dominated by CHON products, suggesting that chemical composition and calculation choices directly influence the mechanism interpretation of SOA oxidation.

Comparisons of average across FIGAERO-CIMS, UHPLC-HRMS and HR-ToF-AMS further reveal systematic discrepancies in this study. Both FIGAERO-CIMS and UHPLC-HRMS could identify the molecule composition, including the CHON species, whereas the HR-ToF-AMS cannot resolve nitrogen-containing species. This limitation likely results in CHON signals being misclassified as CHO, leading to the introduction of systematic biases in to O C and, thereby, the calculation of .

Beyond instrument-specific biases, the mixed-precursor experiments highlight that the precursor interactions, such as OH scavenging by isoprene, NOx-driven RO2 competition and cross-interactions between RO2 from different precursors, could change the balance of functionalisation and fragmentation, producing average trajectories that are distinct from those of single VOCs.

All the data used in this work can be accessed through the open database of the EUROCHAMP programme (https://data.eurochamp.org/data-access/chamber-experiments, last access: 4 December 2025) (https://doi.org/10.25326/HNCK-KE85; McFiggans, et al., 2020).

The supplement related to this article is available online at https://doi.org/10.5194/ar-3-619-2025-supplement.

GM, MRA, AV, YW and YS conceived the study. AV, YW, YS and MD conducted the experiments. TJB provided technical assistance during the experiments and contributed to the FIGAERO-CIMS data analysis. YS conducted the data analysis and wrote the paper, with contributions from all of the co-authors.

The contact author has declared that none of the authors has any competing interests.

Publisher's note: Copernicus Publications remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims made in the text, published maps, institutional affiliations, or any other geographical representation in this paper. While Copernicus Publications makes every effort to include appropriate place names, the final responsibility lies with the authors. Views expressed in the text are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the publisher.

Yunqi Shao would like to thank Kelly Pereira for on-site UHPLC-HRMS training, for filter analysis and for providing the automated non-targeted UHPLCHRMS method. Yunqi Shao also acknowledges the use of the ChatGPT AI tool for proofreading and grammar correction during the final stages of manuscript preparation, which Yunqi Shao reviewed, edited and takes full responsibility for. All of the final wording reflects Yunqi Shao's own edits and judgement.

This study received funding from the European Union's Horizon 2020 research and innovation programme under grant agreement no. 730997 (EUROCHAMP2020). Instrumentation support was provided by the NERC Atmospheric Measurement and Observation Facility (AMOF). Yu Wang acknowledges support from the joint scholarship of The University of Manchester and the China Scholarship Council. M. Rami Alfarra acknowledges support from the UK National Centre for Atmospheric Science (NCAS). Aristeidis Voliotis acknowledges support from the NERC EAO Doctoral Training Partnership.

This paper was edited by Annele Virtanen and reviewed by two anonymous referees.

Ahlberg, E., Falk, J., Eriksson, A., Holst, T., Brune, W. H., Kristensson, A., Roldin, P., and Svenningsson, B.: Secondary organic aerosol from VOC mixtures in an oxidation flow reactor, Atmospheric Environment, 161, 210–220, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.atmosenv.2017.05.005, 2017.

Aiken, A. C., DeCarlo, P. F., Kroll, J. H., Worsnop, D. R., Huffman, J. A., Docherty, K. S., Ulbrich, I. M., Mohr, C., Kimmel, J. R., Sueper, D., Sun, Y., Zhang, Q., Trimborn, A., Northway, M., Ziemann, P. J., Canagaratna, M. R., Onasch, T. B., Alfarra, M. R., Prevot, A. S. H., Dommen, J., Duplissy, J., Metzger, A., Baltensperger, U., and Jimenez, J. L.: O C and OM OC Ratios of Primary, Secondary, and Ambient Organic Aerosols with High-Resolution Time-of-Flight Aerosol Mass Spectrometry, Environmental Science & Technology, 42, 4478–4485, https://doi.org/10.1021/es703009q, 2008.

Alfarra, M. R., Coe, H., Allan, J. D., Bower, K. N., Boudries, H., Canagaratna, M. R., Jimenez, J. L., Jayne, J. T., Garforth, A. A., Li, S.-M., and Worsnop, D. R.: Characterization of urban and rural organic particulate in the Lower Fraser Valley using two Aerodyne Aerosol Mass Spectrometers, Atmospheric Environment, 38, 5745–5758, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.atmosenv.2004.01.054, 2004.

Atkinson, R., Baulch, D. L., Cox, R. A., Crowley, J. N., Hampson, R. F., Hynes, R. G., Jenkin, M. E., Rossi, M. J., and Troe, J.: Evaluated kinetic and photochemical data for atmospheric chemistry: Volume I - gas phase reactions of Ox, HOx, NOx and SOx species, Atmos. Chem. Phys., 4, 1461–1738, https://doi.org/10.5194/acp-4-1461-2004, 2004.

Bruns, E. A., Perraud, V., Zelenyuk, A., Ezell, M. J., Johnson, S. N., Yu, Y., Imre, D., Finlayson-Pitts, B. J., and Alexander, M. L.: Comparison of FTIR and Particle Mass Spectrometry for the Measurement of Particulate Organic Nitrates, Environmental Science & Technology, 44, 1056–1061, https://doi.org/10.1021/es9029864, 2010.

Carlton, A. G., Wiedinmyer, C., and Kroll, J. H.: A review of Secondary Organic Aerosol (SOA) formation from isoprene, Atmos. Chem. Phys., 9, 4987–5005, https://doi.org/10.5194/acp-9-4987-2009, 2009.

Chen, X., Li, K., Li, R., Fang, L., Bian, H., Jiang, W., Yan, C., and Du, L.: NOx-driven chemical transformation of terpene mixtures: Linking highly oxygenated organic molecules to health effects in secondary organic aerosol, Journal of Environmental Sciences, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jes.2025.09.004, 2025.

Chhabra, P. S., Flagan, R. C., and Seinfeld, J. H.: Elemental analysis of chamber organic aerosol using an aerodyne high-resolution aerosol mass spectrometer, Atmos. Chem. Phys., 10, 4111–4131, https://doi.org/10.5194/acp-10-4111-2010, 2010.

Cui, Y., Chen, K., Zhang, H., Lin, Y.-H., and Bahreini, R.: Chemical Composition and Optical Properties of Secondary Organic Aerosol from Photooxidation of Volatile Organic Compound Mixtures, ACS ES&T Air, 1, 247–258, https://doi.org/10.1021/acsestair.3c00041, 2024.

D'Ambro, E. L., Schobesberger, S., Gaston, C. J., Lopez-Hilfiker, F. D., Lee, B. H., Liu, J., Zelenyuk, A., Bell, D., Cappa, C. D., Helgestad, T., Li, Z., Guenther, A., Wang, J., Wise, M., Caylor, R., Surratt, J. D., Riedel, T., Hyttinen, N., Salo, V.-T., Hasan, G., Kurtén, T., Shilling, J. E., and Thornton, J. A.: Chamber-based insights into the factors controlling epoxydiol (IEPOX) secondary organic aerosol (SOA) yield, composition, and volatility, Atmos. Chem. Phys., 19, 11253–11265, https://doi.org/10.5194/acp-19-11253-2019, 2019.

Daumit, K. E., Kessler, S. H., and Kroll, J. H.: Average chemical properties and potential formation pathways of highly oxidized organic aerosol, Faraday Discuss, 165, 181–202, https://doi.org/10.1039/c3fd00045a, 2013.

DeCarlo, P. F., Kimmel, J. R., Trimborn, A., Northway, M. J., Jayne, J. T., Aiken, A. C., Gonin, M., Fuhrer, K., Horvath, T., Docherty, K. S., Worsnop, D. R., and Jimenez, J. L.: Field-Deployable, High-Resolution, Time-of-Flight Aerosol Mass Spectrometer, Analytical Chemistry, 78, 8281–8289, https://doi.org/10.1021/ac061249n, 2006.

Dillon, T. J., Dulitz, K., Groß, C. B. M., and Crowley, J. N.: Temperature-dependent rate coefficients for the reactions of the hydroxyl radical with the atmospheric biogenics isoprene, alpha-pinene and delta-3-carene, Atmos. Chem. Phys., 17, 15137–15150, https://doi.org/10.5194/acp-17-15137-2017, 2017.

Docherty, K. S., Corse, E. W., Jaoui, M., Offenberg, J. H., Kleindienst, T. E., Krug, J. D., Riedel, T. P., and Lewandowski, M.: Trends in the oxidation and relative volatility of chamber-generated secondary organic aerosol, Aerosol Science and Technology, 52, 992–1004, https://doi.org/10.1080/02786826.2018.1500014, 2018.

Du, M., Voliotis, A., Shao, Y., Wang, Y., Bannan, T. J., Pereira, K. L., Hamilton, J. F., Percival, C. J., Alfarra, M. R., and McFiggans, G.: Combined application of online FIGAERO-CIMS and offline LC-Orbitrap mass spectrometry (MS) to characterize the chemical composition of secondary organic aerosol (SOA) in smog chamber studies, Atmos. Meas. Tech., 15, 4385–4406, https://doi.org/10.5194/amt-15-4385-2022, 2022.

Eddingsaas, N. C., Loza, C. L., Yee, L. D., Chan, M., Schilling, K. A., Chhabra, P. S., Seinfeld, J. H., and Wennberg, P. O.: α-pinene photooxidation under controlled chemical conditions – Part 2: SOA yield and composition in low- and high-NOx environments, Atmos. Chem. Phys., 12, 7413–7427, https://doi.org/10.5194/acp-12-7413-2012, 2012.

Fry, J. L., Kiendler-Scharr, A., Rollins, A. W., Wooldridge, P. J., Brown, S. S., Fuchs, H., Dubé, W., Mensah, A., dal Maso, M., Tillmann, R., Dorn, H.-P., Brauers, T., and Cohen, R. C.: Organic nitrate and secondary organic aerosol yield from NO3 oxidation of β-pinene evaluated using a gas-phase kinetics/aerosol partitioning model, Atmos. Chem. Phys., 9, 1431–1449, https://doi.org/10.5194/acp-9-1431-2009, 2009.

Han, S., Li, Z., Lau, Y. S., Xiao, Y., Miljevic, B., Horchler, J., Li, J., Hu, W.-P., Wang, H., Wang, B., and Ristovski, Z.: Unraveling secondary organic aerosol formation from isoprene and toluene mixture, npj Climate and Atmospheric Science, 8, 311, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41612-025-01189-4, 2025.

Hildebrandt, L., Henry, K. M., Kroll, J. H., Worsnop, D. R., Pandis, S. N., and Donahue, N. M.: Evaluating the Mixing of Organic Aerosol Components Using High-Resolution Aerosol Mass Spectrometry, Environmental Science & Technology, 45, 6329–6335, https://doi.org/10.1021/es200825g, 2011.

Hoffmann, T., Odum, J. R., Bowman, F., Collins, D., Klockow, D., Flagan, R. C., and Seinfeld, J. H.: Formation of Organic Aerosols from the Oxidation of Biogenic Hydrocarbons, Journal of Atmospheric Chemistry, 26, 189–222, https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1005734301837, 1997.

Hoffmann, T., Huang, R.-J., and Kalberer, M.: Atmospheric Analytical Chemistry, Analytical Chemistry, 83, 4649–4664, https://doi.org/10.1021/ac2010718, 2011.

Jayne, J. T., Leard, D. C., Zhang, X., Davidovits, P., Smith, K. A., Kolb, C. E., and Worsnop, D. R.: Development of an aerosol mass spectrometer for size and composition analysis of submicron particles, Aerosol Science & Technology, 33, 49–70, 2000.

Jimenez, J. L., Jayne, J. T., Shi, Q., Kolb, C. E., Worsnop, D. R., Yourshaw, I., Seinfeld, J. H., Flagan, R. C., Zhang, X., Smith, K. A., Morris, J. W., and Davidovits, P.: Ambient aerosol sampling using the Aerodyne Aerosol Mass Spectrometer, Journal of Geophysical Research: Atmospheres, 108, https://doi.org/10.1029/2001JD001213, 2003.

Kroll, J. H., Ng, N. L., Murphy, S. M., Flagan, R. C., and Seinfeld, J. H.: Secondary organic aerosol formation from isoprene photooxidation under high-NOx conditions, Geophysical Research Letters, 32, https://doi.org/10.1029/2005GL023637, 2005a.

Kroll, J. H., Ng, N. L., Murphy, S. M., Varutbangkul, V., Flagan, R. C., and Seinfeld, J. H.: Chamber studies of secondary organic aerosol growth by reactive uptake of simple carbonyl compounds, Journal of Geophysical Research: Atmospheres, 110, https://doi.org/10.1029/2005JD006004, 2005b.

Kroll, J. H., Donahue, N. M., Jimenez, J. L., Kessler, S. H., Canagaratna, M. R., Wilson, K. R., Altieri, K. E., Mazzoleni, L. R., Wozniak, A. S., Bluhm, H., Mysak, E. R., Smith, J. D., Kolb, C. E., and Worsnop, D. R.: Carbon oxidation state as a metric for describing the chemistry of atmospheric organic aerosol, Nature Chemistry, 3, 133–139, https://doi.org/10.1038/nchem.948, 2011.

Kroll, J. H., Lim, C. Y., Kessler, S. H., and Wilson, K. R.: Heterogeneous Oxidation of Atmospheric Organic Aerosol: Kinetics of Changes to the Amount and Oxidation State of Particle-Phase Organic Carbon, The Journal of Physical Chemistry A, 119, 10767–10783, https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.jpca.5b06946, 2015.

Lee, B.-H., Pierce, J. R., Engelhart, G. J., and Pandis, S. N.: Volatility of secondary organic aerosol from the ozonolysis of monoterpenes, Atmospheric Environment, 45, 2443–2452, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.atmosenv.2011.02.004, 2011.

Lee, B. H., Lopez-Hilfiker, F. D., Mohr, C., Kurtén, T., Worsnop, D. R., and Thornton, J. A.: An Iodide-Adduct High-Resolution Time-of-Flight Chemical-Ionization Mass Spectrometer: Application to Atmospheric Inorganic and Organic Compounds, Environmental Science & Technology, 48, 6309–6317, https://doi.org/10.1021/es500362a, 2014.

Li, K., Zhang, X., Zhao, B., Bloss, W. J., Lin, C., White, S., Yu, H., Chen, L., Geng, C., Yang, W., Azzi, M., George, C., and Bai, Z.: Suppression of anthropogenic secondary organic aerosol formation by isoprene, npj Climate and Atmospheric Science, 5, 12, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41612-022-00233-x, 2022.

Lopez-Hilfiker, F. D., Mohr, C., Ehn, M., Rubach, F., Kleist, E., Wildt, J., Mentel, Th. F., Lutz, A., Hallquist, M., Worsnop, D., and Thornton, J. A.: A novel method for online analysis of gas and particle composition: description and evaluation of a Filter Inlet for Gases and AEROsols (FIGAERO), Atmos. Meas. Tech., 7, 983–1001, https://doi.org/10.5194/amt-7-983-2014, 2014.

McFiggans, G., Mentel, T. F., Wildt, J., Pullinen, I., Kang, S., Kleist, E., Schmitt, S., Springer, M., Tillmann, R., and Wu, C.: Secondary organic aerosol reduced by mixture of atmospheric vapours, Nature, 565, 587, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-018-0871-y, 2019.

McFiggans, G.: Atmospheric simulation chamber study: alpha-pinene + ortho-cresol + isoprene + OH – Aerosol study – particle formation – 2019-07-19 (Version 1.0), AERIS [dataset], https://doi.org/10.25326/HNCK-KE85, 2020.

Pandis, S. N., Paulson, S. E., Seinfeld, J. H., and Flagan, R. C.: Aerosol formation in the photooxidation of isoprene and β-pinene, Atmospheric Environment. Part A. General Topics, 25, 997–1008, https://doi.org/10.1016/0960-1686(91)90141-S, 1991.

Pereira, K., Ward, M., Wilkinson, J., Sallach, J., Bryant, D., Dixon, W., Hamilton, J., and Lewis, A.: An Automated Methodology for Non-targeted Compositional Analysis of Small Molecules in High Complexity Environmental Matrices Using Coupled Ultra Performance Liquid Chromatography Orbitrap Mass Spectrometry, Environmental Science & Technology, https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.est.0c08208, 2021.

Presto, A. A., Miracolo, M. A., Kroll, J. H., Worsnop, D. R., Robinson, A. L., and Donahue, N. M.: Intermediate-Volatility Organic Compounds: A Potential Source of Ambient Oxidized Organic Aerosol, Environmental Science & Technology, 43, 4744–4749, https://doi.org/10.1021/es803219q, 2009.

Pullinen, I., Schmitt, S., Kang, S., Sarrafzadeh, M., Schlag, P., Andres, S., Kleist, E., Mentel, T. F., Rohrer, F., Springer, M., Tillmann, R., Wildt, J., Wu, C., Zhao, D., Wahner, A., and Kiendler-Scharr, A.: Impact of NOx on secondary organic aerosol (SOA) formation from α-pinene and β-pinene photooxidation: the role of highly oxygenated organic nitrates, Atmos. Chem. Phys., 20, 10125–10147, https://doi.org/10.5194/acp-20-10125-2020, 2020.

Shao, Y., Voliotis, A., Du, M., Wang, Y., Pereira, K., Hamilton, J., Alfarra, M. R., and McFiggans, G.: Chemical composition of secondary organic aerosol particles formed from mixtures of anthropogenic and biogenic precursors, Atmos. Chem. Phys., 22, 9799–9826, https://doi.org/10.5194/acp-22-9799-2022, 2022a.

Shao, Y., Wang, Y., Du, M., Voliotis, A., Alfarra, M. R., O'Meara, S. P., Turner, S. F., and McFiggans, G.: Characterisation of the Manchester Aerosol Chamber facility, Atmos. Meas. Tech., 15, 539–559, https://doi.org/10.5194/amt-15-539-2022, 2022b.

Shilling, J. E., Chen, Q., King, S. M., Rosenoern, T., Kroll, J. H., Worsnop, D. R., DeCarlo, P. F., Aiken, A. C., Sueper, D., Jimenez, J. L., and Martin, S. T.: Loading-dependent elemental composition of α-pinene SOA particles, Atmos. Chem. Phys., 9, 771–782, https://doi.org/10.5194/acp-9-771-2009, 2009.

Stark, H., Yatavelli, R. L. N., Thompson, S. L., Kimmel, J. R., Cubison, M. J., Chhabra, P. S., Canagaratna, M. R., Jayne, J. T., Worsnop, D. R., and Jimenez, J. L.: Methods to extract molecular and bulk chemical information from series of complex mass spectra with limited mass resolution, International Journal of Mass Spectrometry, 389, 26–38, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijms.2015.08.011, 2015.

Stroud, C. A., Roberts, J. M., Goldan, P. D., Kuster, W. C., Murphy, P. C., Williams, E. J., Hereid, D., Parrish, D., Sueper, D., Trainer, M., Fehsenfeld, F. C., Apel, E. C., Riemer, D., Wert, B., Henry, B., Fried, A., Martinez-Harder, M., Harder, H., Brune, W. H., Li, G., Xie, H., and Young, V. L.: Isoprene and its oxidation products, methacrolein and methylvinyl ketone, at an urban forested site during the 1999 Southern Oxidants Study, Journal of Geophysical Research: Atmospheres, 106, 8035–8046, https://doi.org/10.1029/2000JD900628, 2001.

Sueper, D. and collaborators: ToF-AMS Data Analysis Software, University of Colorado Boulder, http://cires1.colorado.edu/jimenez-group/wiki/index.php/ToF-AMS_Analysis_Software (last access: 3 December 2025), 2023.

Surratt, J. D., Kroll, J. H., Kleindienst, T. E., Edney, E. O., Claeys, M., Sorooshian, A., Ng, N. L., Offenberg, J. H., Lewandowski, M., Jaoui, M., Flagan, R. C., and Seinfeld, J. H.: Evidence for Organosulfates in Secondary Organic Aerosol, Environmental Science & Technology, 41, 517–527, https://doi.org/10.1021/es062081q, 2007.

Surratt, J. D., Gómez-González, Y., Chan, A. W. H., Vermeylen, R., Shahgholi, M., Kleindienst, T. E., Edney, E. O., Offenberg, J. H., Lewandowski, M., Jaoui, M., Maenhaut, W., Claeys, M., Flagan, R. C., and Seinfeld, J. H.: Organosulfate Formation in Biogenic Secondary Organic Aerosol, The Journal of Physical Chemistry A, 112, 8345–8378, https://doi.org/10.1021/jp802310p, 2008.

Voliotis, A., Wang, Y., Shao, Y., Du, M., Bannan, T. J., Percival, C. J., Pandis, S. N., Alfarra, M. R., and McFiggans, G.: Exploring the composition and volatility of secondary organic aerosols in mixed anthropogenic and biogenic precursor systems, Atmos. Chem. Phys., 21, 14251–14273, https://doi.org/10.5194/acp-21-14251-2021, 2021.

Voliotis, A., Du, M., Wang, Y., Shao, Y., Bannan, T. J., Flynn, M., Pandis, S. N., Percival, C. J., Alfarra, M. R., and McFiggans, G.: The influence of the addition of isoprene on the volatility of particles formed from the photo-oxidation of anthropogenic–biogenic mixtures, Atmos. Chem. Phys., 22, 13677–13693, https://doi.org/10.5194/acp-22-13677-2022, 2022a.

Voliotis, A., Du, M., Wang, Y., Shao, Y., Alfarra, M. R., Bannan, T. J., Hu, D., Pereira, K. L., Hamilton, J. F., Hallquist, M., Mentel, T. F., and McFiggans, G.: Chamber investigation of the formation and transformation of secondary organic aerosol in mixtures of biogenic and anthropogenic volatile organic compounds, Atmos. Chem. Phys., 22, 14147–14175, https://doi.org/10.5194/acp-22-14147-2022, 2022b.