the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 License.

the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 License.

Primary particle emissions and atmospheric secondary aerosol formation potential from a large-scale wood-pellet-fired heating plant

Fanni Mylläri

Niina Kuittinen

Minna Aurela

Teemu Lepistö

Paavo Heikkilä

Laura Salo

Lassi Markkula

Panu Karjalainen

Joel Kuula

Sami Harni

Katriina Kyllönen

Satu Similä

Katriina Kirvelä

Joakim Autio

Marko Palonen

Jouni Valtatie

Anna Häyrinen

Hilkka Timonen

Solid biofuels are one option to reduce fossil fuel combustion and mitigate climate change. However, large-scale combustion of solid biofuels can have significant impacts on air quality and the emissions of short-lived climate forcers. Due to the lack of detailed scientific experimental data on aerosol emissions, these atmospheric emissions and their aerosol impacts are largely unknown. In this study, we characterized primary particle emissions before and after the flue gas cleaning, as well as the potential of emissions to form secondary particulate mass in the atmosphere from the compounds emitted from a large-scale, biomass-fired modern heating plant. Experiments were conducted at three power plant loads, i.e., 30, 60, and 100 MW (full load), and, at each of these loads, flue gas particles were characterized for their physical and chemical characteristics. The study highlights the importance of efficient flue gas cleaning in biofuel applications; the bag-house filters (BHFs) utilized to clean the flue gas from the combustion boiler reduced the particle number emissions by 3 orders of magnitude, and the black carbon (BC) emissions were close to zero. After the filtration, at 30, 60, and 100 MW, the measured primary particle number emissions were 1.7 × 103, 5.2 × 103, and 7.2 × 103 MJ−1, respectively. By number, emitted particles existed mostly in the sub-200 nm mobility particle size range. When measuring the potential of flue gas to form secondary aerosol in the atmosphere, for the first time, according to the authors' knowledge, we observed that the secondary aerosol formation potential of flue gas is high; the total impact of flue gases on atmospheric particulate matter concentrations can even be 100 to 1000 times higher than the impact of primary particle emissions. In general, the results of the study enable emission inventory updates, improved air quality assessments, and climate modeling to support the transition toward climate-neutral societies.

- Article

(1175 KB) - Full-text XML

-

Supplement

(646 KB) - BibTeX

- EndNote

Climate change can be mitigated either by adopting CO2-neutral fuels in energy production or by producing energy from other renewable sources. According to the International Energy Agency (IEA) (2020), the fastest-growing installed power generation capacity is currently wind and solar photovoltages (PVs). This new power generation capacity is a substitute for coal and oil combustion (IEA, 2020; Bloomberg, 2020). Adopting non-combustion sources of electricity production can lead to substantial changes in power production, possibly even leading to shutdowns of non-profitable fossil-fuel-based power plants. In the case of combined heat and power plants (CHPs), this can cause additional demand due to the required production of heat for district heating. Heat can be produced, e.g., in heating plants relying on biomass combustion or with geothermal heat pumps. In addition to wind and solar power, the use of other renewable power generation sources, such as biomass, is currently increasing (IEA 2020).

In addition to CO2 emissions, combustion processes of carbon-based fuels emit particles and other gaseous compounds such as NOx and CO that can significantly deteriorate air quality and affect the climate (Guevara et al., 2024; Jiang et al., 2024). Regarding small- and medium-scale boilers, previous biomass combustion studies have shown that particle emission factors can vary significantly; for example, in a study by Sippula et al. (2009a), the particulate mass of particles with a diameter smaller than 1 µm (PM1) varied from 3.9 to 92 mg MJ−1, depending on the cleaning systems applied to the flue gas. For particle number concentration, the variation was from 1.2 × 1013 to 76 × 1013 particles MJ−1. In these same experiments conducted on combustion appliances with a nominal power of 20 kW through 15 MW, the total carbon fraction (organic carbon (OC) + elemental carbon (EC)) in fine particles was below 6 mg MJ−1, and it constituted 0.8 %–22 % of the fine particles (Sippula et al., 2009a–c). In an article by Lamberg et al., the PM1 emission factors for a household pellet boiler (25 kW) were 12.2–16.3 mg MJ−1, corresponding to 100 % load and 28 % load (Lamberg et al., 2011). In the research by Schmidt et al. (2018), the emission factor for PN< 2.5 µm was 3.64 ± 0.006 × 1013 MJ−1, and the emission factor for the total suspended particles (TSPs) was 14–57 mg MJ−1 for a boiler with a nominal power of 1.3–6.3 kW. It should be noticed that the flue gas cleaning has remarkable effects on the emission factors; e.g., in Sippula et al. (2009a), the highest particle emission factors (92 mg MJ−1) were obtained for the situation without exhaust cleaning, and the situation when the electrostatic precipitators were used led to a reduction of more than 1 order of magnitude in PM1 emissions.

Furthermore, few studies have focused on the characterization of the physical and chemical properties of particles emitted by heating plants and devices. Strand et al. (2002) reported an average geometric mean diameter of the flue gas particles to be 88 nm before electrostatic precipitation (ESP) and 127 nm after ESP in the 6 MW grate boiler heating plant. Another study by Löndahl et al. (2008) reported that, irrespective of the biomass combustion conditions, the particle count median mobility diameter was 81 nm for complete and 137 nm for incomplete combustion. Regarding the particle composition measured from small-scale boilers, Sippula et al. (2007) reported that the PM1 mass emitted from the combustion of commercial wood pellets consisted of K2SO4 (40 %), K2CO3 (15 %), organic matter (15 %), and other compounds (10 %), and the rest of the particle mass contained KCl, KNO3, Na2CO3, KOH, and EC. Lamberg et al. (2011) reported that decreasing the boiler load increased PM1 emissions and that most of this increase originated from EC, which indicates incomplete combustion.

In addition to primary particles, combustion processes frequently emit gaseous precursor compounds that have the potential to form secondary particulate matter in the atmosphere. This atmospheric process is driven by the oxidation of emitted compounds, which can decrease the volatility of compounds and thus enable the condensation of compounds into the particle phase. Stevens et al. (2012) and Mylläri et al. (2016) showed that there is new particle formation in the flue gas plumes of large coal-fired power plants. This indicates that the emitted flue gases can contain precursors for secondary particle formation in the atmosphere. However, to our knowledge, secondary aerosol studies for full-scale power plants fueled by biomass do not exist in the peer-reviewed literature.

Regardless of the differences between large-scale power plant boilers and smaller boilers, some indications of the secondary aerosol formation potential of pellet burning can be found in existing studies utilizing smaller burners or in small-scale biomass combustion studies. For example, in a study by Heringa et al. (2011), the researchers applied a photo-oxidation smog chamber to age the flue gas from a residential pellet burner with a nominal power output of 8 kW. They studied the flue gas formed in the burner under stable combustion conditions and determined that BC contributes 33 % of the total particulate mass of the aged flue gas emissions and that the rest of the particulate mass was primary organic aerosol (POA), which means that secondary organic aerosol (SOA) was not significantly formed in the aging process. In the study of Czech et al. (2017), the secondary aerosol formation potential of the emissions from the pellet burner was also evaluated to be relatively low when compared to log wood stoves, demonstrating pellet boilers to be a relatively clean technology for biomass combustion. Ortega et al. (2013) obtained relatively similar results for biomass which was burned openly on the top of a ceramic plate; the aging of biomass burning smoke in an oxidation flow reactor resulted in a total organic aerosol (OA) average of 1.42 ± 0.36 times the initial POA. In contrast to that, the SOA is typically the largest component of ambient OA, followed by POA from anthropogenic and biogenic sources (Jimenez et al., 2009; Robinson et al., 2007). However, in atmospheric studies, it is difficult to separate secondary aerosol emitted by different anthropogenic sources, and thus the influence of power plants on ambient SOA remains unknown. Regarding the OA emitted by pellet-burning processes, it should be noted that they can contain compounds like toxic polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs) (Hays et al., 2019; Wang et al., 2019), having potentially harmful effects on human health.

Heating plants fueled with pellets are becoming more common in countries with centralized heating systems because they substitute heat sources originating from fossil fuels, such as coal-fired power plants. The emissions of these large-scale, pellet-fired modern heating plants have not been studied in detail even though their emissions can have a substantial impact on local and regional air quality and the climate. Here, we investigated the primary and secondary particulate emissions of a full-scale 100 MW heating plant equipped with bag-house filters (BHFs) and characterized them online with state-of-the-art instrumentation. The heating plant was fueled with wood pellets, and its load was varied (30, 60, and 100 MW). We made primary particle characterization before and after the BHF to obtain information on the filtration efficiency of the BHF system. In addition, after the BHF, we aged the flue gas artificially in an oxidation flow reactor to mimic the atmospheric aging of the flue gas. Besides particle number concentration, PM, and particle number size distributions, we measured the chemical compositions of particles and gas emissions after the flue gas filtration. In addition to the increased understanding of fine-particle emissions from large-scale energy production and related flue gas cleaning systems, the results can be used to estimate the total air quality and climatic effects from biomass-based heating plants.

2.1 Power plant and fuel

We performed the study at the Salmisaari wood-pellet-fired heating plant (in use since 2018) located in Helsinki, Finland. The heating plant is operated according to the heating needs of the central heating grid of the city of Helsinki. We selected loads of 30, 60, and 100 MW (the maximum power) to be the most representative points of operation. The boiler of the heating plant (Valmet Ltd.) has two pellet burners (Saacke Ltd.) that are located on the top of the boiler. More information about the boiler configuration, combustion technology, and combustion process modeling can be found in Niemelä et al. (2022). From the boiler, the flue gas is led through BHFs to the 116 m high stack. Continuous regulatory measurements of gaseous emissions (CO, NOx, SO2) and regulated dust emissions (Sick Dusthunter SP100, EN 15267) of the power plant and flue gas volume flow, done by the power plant operator, are conducted through probes located in the stack at a height of approximately 25 m. The dust concentration measurement is based on the EN 15267 standard, and it is calibrated according to the SFS-EN 13284-1 standard. We determined the first measurement location before the BHF to study the filtration efficiency of the BHF (see measurement setup in Fig. S1a in the Supplement). We made the aerosol measurements after the BHF from the same measurement location as the continuous regulatory measurements (see the measurement setup in Fig. S1b).

The wood pellets combusted during the campaign came from two different suppliers but were of the same quality (for more details on the pellets, see Table S1 in the Supplement and, e.g., Chandrasekaran et al., 2012). They had relatively similar chemical compositions; the most significant differences were in the potassium (K), phosphorus (P), sulfur (S), silicon (Si), and calcium (Ca) concentrations. We fed the pellets into the burners from a pellet silo through two mills. The ratio of the two pellet types could not be determined during the measurements. Depending on the load of the boiler, the wood pellet consumption was between 6 and 21 t h−1.

In the heating plant, the flue gas from the boiler is conveyed to the BHF to separate fly ash and other particles from the flue gas stream. The BHF consists of four separate compartments. In the BHF, the flue gas flows through the vertically installed filter bags, leaving fly ash, dust, and additives on the outer surface of the bags. The cleaned gas then flows upwards inside the filter bags and, finally, to the stack. The filter bags are periodically cleaned by means of compressed air pulses. The cleaning pulse releases the accumulated particles from filter bags into the ash hopper, located at the bottom of each compartment. From the hopper, the collected material is discharged using pneumatic transmitters into the fly ash silo. In the calculation of this study's results, the possible effects of cleaning periods are included in the reported emissions as the BHF cleaning belongs to the normal operation of the heating plant.

2.2 Measurement setup

The measurement setup before the BHF (see Fig. S1a) was used as a reference for the measurement after the BHF and gave insight into the potential emissions of a heating plant in case it is operated without the BHF. From that measurement point, we sampled the flue gas and diluted it with a porous tube diluter (PTD, Mikkanen et al., 2001; Ntziachristos et al., 2004) (dilution air temperature set to 30 °C, dilution ratio set to 12), followed by a residence time tube to mimic the potential nanoparticle formation during atmospheric dilution of the aerosol (Rönkkö et al., 2006; Keskinen and Rönkkö, 2010). After the residence time tube, we further diluted the sample with an ejector diluter (Dekati Ltd.) before the aerosol instruments. We characterized the particles in the diluted flue gas sample with a Scanning Mobility Particle Sizer (SMPS) (DMA3081 and CPC3776, 1.5 L min−1/6 L min−1 sample/sheath flow, TSI Inc., Wang and Flagan, 1990), a condensation particle counter (CPC, UCPC3776, TSI Inc.), and an electrical low-pressure impactor (ELPI, Dekati Ltd., Keskinen et al., 1992), modified with an additional stage (Yli-Ojanperä et al., 2010) and a filter stage (Marjamäki et al., 2002). We added a bifurcated flow diluter before the CPC to lower the particle number concentrations to the measurement range of the CPC. We measured the black carbon (BC) concentrations using one sensor type instrument (a micro-aethalometer; mAE 200, Aethlabs, US). We monitored the dilution ratio of the flue gas sample with a CO2 analyzer (Sick Maihak v. 2.0, Sidor) before and after the ejector diluter. Between the residence time tube and the ejector diluter, there was a possibility to use a catalytic stripper (CS, Amanatidis et al., 2013) to remove the volatile components from the particles. The line losses for them were approximately 20 % at the 10 nm particle size, less than 5 % at 30 nm, and 2 % at 100 nm. The results from measurements before BHF have been briefly described in Niemelä et al. (2022).

In the measurement setup after the BHF (Fig. S1b), the flue gas sample was sampled and diluted from the stack using a fine-particle sampler (FPS, Dekati Ltd., Mikkanen et al., 2001). The temperature of the FPS was adjusted to 30 °C, and the primary dilution ratio was around 12. After dilution, the sample was led to the instruments installed in the Aerosol and Trace gas Mobile Laboratory (ATMo-Lab) of Tampere University (see Rönkkö et al., 2017) with a 100 slpm flow by means of an insulated 20.6 m long sampling line (12 mm inner diameter). The excess of sample flow was removed before the sample was led through the ATMo-Lab's roof to the instruments. Line losses for particles were approximately 60 % at 10 nm particle size, 10 % at 50 nm, and less than 5 % at 100 nm.

We measured the concentrations of particulate and gaseous compounds in the diluted flue gas sample with various gas and aerosol instruments. The aerosol instrumentation included a CPC (UCPC3776, TSI Inc.), an SMPS (DMA3081 and CPC3775, 1.5 L min−1/6 L min−1 sample/sheath flow, TSI Inc., Wang and Flagan, 1990), an electrical low-pressure impactor (ELPI, Dekati Ltd., Keskinen et al., 1992) modified with an additional stage (Yli-Ojanperä et al., 2010) and a filter stage (Marjamäki et al., 2002), and a soot particle aerosol mass spectrometer (SP-AMS, Aerodyne Research Inc., Onasch et al., 2012) to study the number concentration, size distribution, and chemical composition (i.e., sulfate, nitrate, ammonium, chloride (Chl), refractory black carbon (rBC), and organic fraction (OA)) of the aerosol particles. In addition, we used an aethalometer (AE33, Magee Scientific, Drinovec et al., 2015) to measure the BC concentration. We measured with the CPCs and ELPI with 1 Hz frequency. The SMPS measured the particle number size distribution every 3 min, whereas the SP-AMS had a 2 min, and the AE33 had a 1 min time resolution in the measurements.

We studied the secondary particle formation potential of the flue gas using a Tampere secondary aerosol reactor (TSAR, Simonen et al., 2017). During that process, we led the diluted sample through the TSAR chamber using a three-way valve. We further diluted the flue gas sample aged in TSAR with an additional clean-air flow using a mass flow controller (MFC, Alicat). After this dilution, we led the sample to the ELPI, SP-AMS, and AE33, which we installed so that they would measure either the primary flue gas sample or the aged flue gas sample, depending on the setting of the abovementioned three-way valve.

In addition to the particle measurements, we measured the CO2 concentration (SICK Maihak v. 2.0, Sidor; analyzer LI-840A, LI-COR) from two different positions (see Fig. 1b) to calculate the dilution ratios of the FPS and the ejector after the TSAR. We used controlled CO addition upstream the TSAR and measured the CO concentration (CO12M, Environnement S.A.) right after the TSAR chamber to calculate the OH exposure of the flue gas sample in the TSAR (Li et al., 2015). We measured the O3 concentration (Model 205, 2B Technologies) at the same point as the ELPI, SP-AMS, and AE33. Additionally, we measured the total hydrocarbon concentration (THC, Series 9000 NMHC Methane/Non-Methane Analyzer, Baseline-Mocon Inc.) and mercury (Model 2537A Hg analyzer, Tekran) next to the SMPS and the CPC. For mercury, the analyzer setup removed the particles in the sample stream with a polytetrafluoroethylene (PTFE) membrane filter (47 mm, 0.2 µm); thus, we measured the total gaseous mercury that consists of both elemental and gaseous oxidized mercury (Kyllönen et al., 2012).

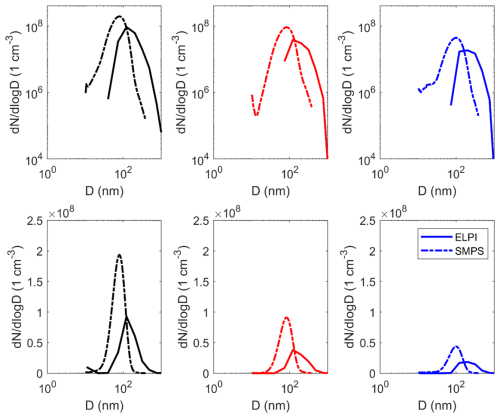

Figure 1The particle number size distributions calculated from the ELPI data (solid line, aerodynamic diameter) and SMPS data (dashed line, mobility diameter) measured before the BHF at three different loads (100, 60, and 30 MW). The distributions are shown with a logarithmic y axis in the upper panel and a linear y axis in the lower panel. The results have been corrected with dilution ratios.

3.1 Flue gas particle characteristics before the BHF

Figure 1 shows the flue gas particle number size distributions measured from the diluted sample before the BHF. In general, the observed particle number size distributions measured were unimodal regardless of whether the size distribution was measured with the ELPI or SMPS. The differences in the median diameters of the particle number size distributions measured by ELPI and SMPS (see Fig. 1) were caused by the different measurement principles of the instruments; while the ELPI classifies the particles based on their aerodynamic diameters, the SMPS classifies the particles based on their mobility diameters. The difference between these diameters is the effective density (ρeff) of the particles, which takes into account the density of the particulate material and the shape of the particles (Ristimäki et al., 2002). We calculated the effective densities of the particles at the peak sizes of size distributions in Table S2 based on the median diameters of particle number size distributions in Fig. 1. In the experiments, the median diameters of the particle number size distributions were the smallest for the 100 MW load (136 nm in the ELPI data and 75 nm in SMPS data) and increased when the load decreased to 30 MW (193 nm in ELPI data and 96 nm in SMPS data). The effective density of the particles was the lowest (2.13 g cm−3) with the highest load of 100 MW, and it was highest (2.55 g cm−3) with the lowest load of 30 MW.

The flue gas particles before the BHF were non-volatile even though the flue gas sampling and dilution system used in this study enabled the condensation and nucleation processes of semi-volatile compounds. This was seen in experiments with the CS, which we used to study the volatility of the particles. The penetration through CS is 70 % for nonvolatile particles over 23 nm in diameter (Amanatidis et al., 2013), and when the particle number size distributions measured after the sample treatment with the CS were corrected with the particle losses in the CS, they were very close to the size distributions measured without the CS (Fig. S1). The median mobility particle diameter was 77 nm for the CS-treated aerosol at 100 and 60 MW loads; thus, they were practically the same compared to the untreated aerosol (see Table S2). Thus, the result indicates that the particles were either solid or at least non-volatile in the studied temperature (300 °C). On the other hand, it indicates that the flue gas before the BHF did not significantly include the compounds that have the potential to condense into the particle phase when the flue gas dilutes and cools.

3.2 Flue gas particle characteristics after the BHF

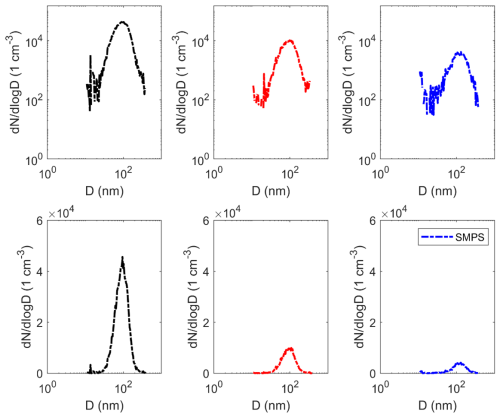

After the BHF (Fig. 2), the maximum peak concentrations of the particle number size distribution were lowered by an approximate factor of 103 compared to the concentrations before the filtration. At the same time, the particle number size distribution measured by the SMPS remained unimodal with the median mobility diameters of the particles at 91, 92, and 120 nm at loads of 100, 60, and 30 MW, respectively.

Figure 2The particle number size distributions measured after the BHF with SMPS (mobility diameter) at three different loads (100, 60, and 30 MW). The distributions are shown with a logarithmic y axis in the upper panel and a linear y axis in the lower panel. The results have been corrected with dilution ratios.

It should also be noted that the median particle diameters measured with SMPS before the BHF were smaller (75–96 nm) than after the BHF, which indicates that the particle collection efficiency of the BHF depends on the particle size. To analyze that, we used the particle size distribution data measured by the SMPS before and after the BHF to determine the collection efficiency of the flue gas filters (Fig. S2). In general, the collection efficiency of the BHF was very high (typically > 0.9995) for particles smaller than 200 nm. However, the filtration efficiency had a clear drop when the particle size increased, being most significant for sizes above 100 nm, which caused the abovementioned change in median particle size. Additionally, it appeared that the drop was the largest for the 100 MW load when the flue gas velocity through the BHF was highest.

3.3 Atmospheric emissions of heating plant

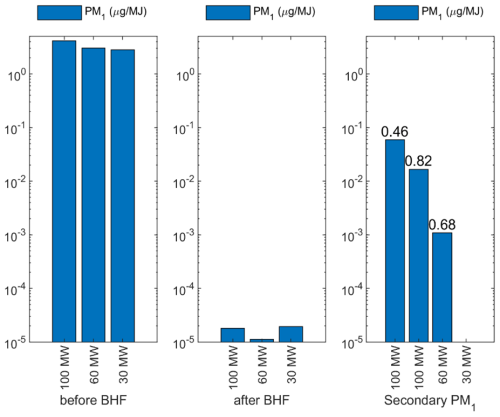

Although the particle concentrations measured before the BHFs do not represent the atmospheric emissions of this particular power plant, those concentrations represent the large-scale heating plant without the flue gas filtration or the situations when the filtration is bypassed. When using the raw flue gas particle number concentrations measured before the BHF by CPC (9.7 × 1013 m−3 at 100 MW, 8.2 × 1012 m−3 at 60 MW, and 6.3 × 1013 m−3 at 30 MW), to calculate the emission factors, the particle number emission factors were 1.7 × 109 MJ−1 (at 100 MW), 1.4 × 108 MJ−1 (at 60 MW), and 1.2 × 109 MJ−1 (at 30 MW). The BC emission factors calculated from mAE data were 3 ng MJ−1 (100 MW), 3 ng MJ−1 (60 MW), and 2 ng MJ−1 (30 MW), calculated from the corresponding raw flue gas BC concentrations of 180, 189, and 87 µg m−3 at 100, 60, and 30 MW, respectively. These emission factor values are significantly lower than the emission factors reported previously for the large-scale coal combustion without efficient flue gas filtration, as well as for the large-scale combustion from the mixture of coal and wood pellets without efficient flue gas filtration (Mylläri et al., 2019). In general, we calculated the emission factors for the particle number and BC shown above and for the mass of particles smaller than 1 µm (PM1), shown below in Fig. 4, using the equation in the supplementary material and a literature value for the CO2 emission factor of wood pellet combustion (112 g CO2 MJ−1; see Statistics of Finland, 2019).

The measurements conducted after the BHFs represent the actual atmospheric emissions of the studied biomass-fueled modern heating plant. We ensured this by using cooling dilution in the flue gas sampling system; in this way, the contribution of semi-volatile compounds to the particle emissions could also be evaluated. The total particle number emission factors, calculated from the raw flue gas concentrations of 1.8 × 1010 m−3 (at 100 MW), 1.1 × 1010 m−3 (at 60 MW), and 3.4 × 109 m−3 (at 30 MW), were 7.2 × 103 MJ−1 (at 100 MW), 5.2 × 103 MJ−1 (at 60 MW), and 1.7 × 103 MJ−1 (at 30 MW). After the BHF, the BC concentrations were below the detection limits of AE33 and SP-AMS, and, thus, we could not calculate any emission factors for the BC after the BHF. In addition to BC, the mass concentrations of other typical chemical components of particulate matter, measured by the SP-AMS, were also very low. For the 60 and 30 MW loads, all of the measured components were close to the concentrations of blank measurements (100 % of synthetic air) or below the determination limits (3× standard deviation of zero points), which were 0.78, 0.52, 0.59, 0.59, 1.89, and 0.96 µg m−3 for sulfate, nitrate, ammonium, Chl, OA, and rBC, respectively, using a dilution ratio of 90 in the sampling system. At a 100 MW load, the observed sulfate and nitrate concentrations after the blank correction were 1.07 and 0.83 µg m−3, respectively, but ammonium and rBC were below the determination limit, and OA and Chl were also very close to the blank concentrations. Furthermore, the gaseous THC concentrations in the diluted flue gas sample were also low and close to the concentrations measured for the pressurized air during the background measurements. Based on this information, the concentration of unburned hydrocarbons could not be estimated in the flue gas. The gaseous Hg concentrations were 0.25 ± 0.02 µg Nm−3 (100 MW), 0.21 ± 0.01 µg Nm−3 (60 MW), and 0.17 ± 0.01 µg Nm−3 (30 MW).

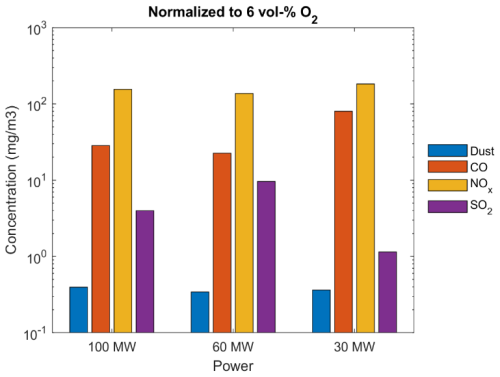

Figure 3 shows the results of continuous regulatory measurements (i.e., dust, CO, NOx, SO2) of the heating plant emissions for each load. We observed the load to have only a minor effect on NOx (approx. 200 mg m−3) and dust (approx. 0.4 mg m−3) emissions of the heating plant. However, the observed CO concentrations were 20–80 mg m−3, and the SO2 concentrations were 1–10 mg m−3, depending on the load. It should be noted that the dust emissions to the atmosphere (i.e., particles, including coarse ones) from the heating plant were significantly affected by the BHF, whereas the BHF did not significantly affect the emissions of gaseous NOx, CO, and SO2. Instead, in the studied heating plant, the emissions of these pollutants may depend mostly on combustion conditions and fuel properties. It should be noted that the dust concentrations (mg m−3) in Fig. 3 cannot be directly compared with the PM1 emissions measured by ELPI (Fig. 4) because of the differences in measurement methods, the particle size ranges covered, and the different sampling used in the measurements.

Figure 3Concentrations of dust, CO, NOx, and SO2 (normalized to 6 vol % O2) from the continuous regulatory measurements of the power plant as a function of the load on a logarithmic scale.

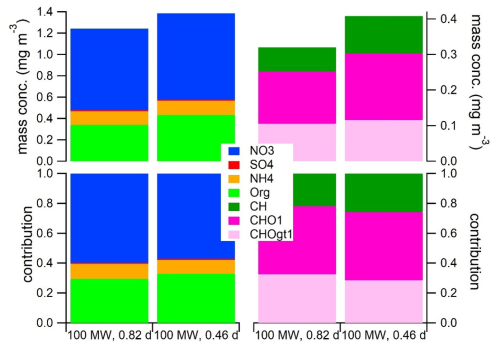

Figure 4PM1 emission factors (µg MJ−1) for the heating plant calculated from ELPI data before the BHF (on the left), after the BHF (in the middle), and after the BHF but treated with TSAR (includes both the primary and secondary PM1, on the right). The numbers above the PM bars, “Secondary PM1” on the right, indicate the OH exposure in the TSAR oxidation flow reactor, converted into approximate atmospheric aging in days. It should be noted that the data for aged flue gas are not available for 30 MW.

In addition to primary particles and delayed primary particulate matter formed during flue gas cooling, the emissions from combustion sources can affect the atmospheric aerosols by means of the secondary particle formation processes (see Rönkkö and Timonen, 2019). In this study, we evaluated the secondary aerosol formation potential of the flue gas using a TSAR, an oxidation flow reactor designed for emission measurements. Figure 4 compares the PM1 emission factors measured before and after the BHF for the fresh emissions (i.e., the emission factors include both the primary and delayed primary particulate matter), with PM1 emission factors calculated from artificially aged flue gas. First, we observed that the BHF decreased the fresh flue gas PM1 emission factor by an approximate factor of 105, which is in line with the results for the high filtration efficiency of the BHF shown above. Second, Fig. 4 shows that the PM1 emission factors increased by a factor of almost 1000 when the secondary aerosol formation potential of the flue gas was included. This means that, even when the flue gas is efficiently cleaned with BHF, the remaining gas phase still has high potential to increase the particle mass concentrations in the atmosphere via photochemical secondary aerosol formation during the aging of the plume. In Fig. 4, the OH exposure of the flue gas sample in the TSAR is shown through the number of days in the atmospheric oxidative conditions above the PM emission factor bars. We applied two different aging conditions (0.46 and 0.82 d) for the 100 MW load, whereas we only subjected the 60 MW load to one aging condition (0.68 d), and the data for the 30 MW are not available.

The particles' chemical composition was affected by the artificial aging of the flue gas. Here we focus on the 100 MW load, where the increase was seen most clearly; as seen in Fig. 4, the mass concentration of particles at the 100 MW load significantly increased during the aging when compared to the fresh emissions. Figure 5 presents the composition of the submicron PM and categorization of the analyzed organic ions into various families representing different chemical compositions for the 100 MW load. For aged particles, the analyzed PM1 mass concentrations (sum of organic compounds, sulfate, ammonium, and nitrate) were 1.24 and 1.39 mg m−3 for the 100 MW load for the atmospheric aging times of 0.82 and 0.46 d, respectively (Fig. 5). Nitrate had the highest mass concentration, followed by organic compounds and ammonium. The sulfate concentration increased only slightly. Chl and rBC could not be determined for aged particles because of the high blank concentration of Chl compared to the sample and because of the interfering ion (HCl) at the same in the rBC analyses. As observed above, the rBC concentration was below the determination limit in fresh particles; this was also seen in measurements of aged flue gas, as expected. In addition, when interpreting particle composition results, it should be kept in mind that the instruments have different particle size ranges covered; e.g., particles in small particle sizes can be outside the range of the composition measurement.

Figure 5Chemical composition (i.e., nitrate, sulfate, ammonium, organics) of the aged particles in an aged flue gas sample and the contributions of various organic groups (CH=CxHy, CHO1=CxHyO, and CHOgt1=CxHyOz, z > 1) to an organic fraction of an aged flue gas aerosol with 100 MW load. Both of the aging scenarios (0.46 and 0.82 d) are shown separately.

We analyzed the organic fraction in more depth by categorizing the analyzed organic ions into different families. The three main families were CxHy (hydrocarbon that contains only carbon and hydrogen atoms), oxygenated hydrocarbon CxHyO (hydrocarbon that contains one oxygen ion), and highly oxygenated hydrocarbon CxHyOz (z > 1, hydrocarbon that contains more than one oxygen ion). The organic fraction after the oxidation flow reactor (OFR) mostly consisted of oxidized organic compounds. However, oxidation at the OFR was relatively mild during the experiments as there was still a relatively large fraction of CxHy ions left (22 %–25 %) after the oxidation. The estimated atmospheric aging was less than a day. The O:C and OM:OC (oxygen to carbon and organic matter to OC) ratios were 1.0 and 2.4 on average, respectively, which resemble the ratios typically measured in an ambient area in Helsinki, Finland (Pirjola et al., 2017).

Due to the drive toward global climate change mitigation, fossil fuel combustion will be replaced by renewable energy sources that may significantly affect anthropogenic aerosol emissions. In this study, we investigated the atmospheric emissions of a large-scale modern heating plant that was fueled by biomass (i.e., wood pellets) and equipped with a BHF unit for flue gas cleaning. We conducted measurements for the flue gas with state-of-the-art aerosol instrumentation in order to quantify the atmospheric aerosol emissions so that we could understand the importance of flue gas cleaning with respect to primary particle emissions, as well as to understand how much the emissions could produce secondary aerosols in the atmosphere.

Based on our aerosol characterization, we conclude that the particle and particle precursor concentrations in the flue gas were low and that their emission factors were very low when compared to, for example, smaller biomass combustion applications (see Sippula et al., 2009a, b). We observed low emissions for the total particle number and mass and separately for particulate BC, sulfate, nitrate, and organics, as well as for gaseous hydrocarbons and semi-volatile compounds that could condense or nucleate to the particle phase when the flue gas dissipates into the atmosphere. This observation is important with respect to the heating plant's potential impact on local air quality. In our study, we mostly observed the flue gas particles in the ultrafine-particle size range (median mobility diameters between 75 and 96 nm, depending on thermal load); thus, we saw the same size range as Mertens et al. (2020) for a 220 MW reconverted, pulverized fuel plant fueled with wood pellets and equipped with dry ESP; this is also the same size range as that of Löndahl et al. (2008). Instead, the median particle sizes were significantly smaller than those reported by previous studies for an incomplete combustion process (e.g., Löndahl et al., 2008). In general, the size of particles is an important factor, e.g., in lung deposition, and recent studies emphasize the role of smaller particles in potential health impacts caused by particulate pollutants (e.g., Lepistö et al., 2023). Importantly, the total impact of emitted flue gases requires even more detailed characterization of pollutants. For example, gaseous emission constituents should be investigated in future studies more comprehensively, e.g., from a secondary aerosol precursor point of view.

This study indicated that the low particle and particle precursor emissions resulted from (a) efficient combustion of the fuel and (b) efficient filtration of the flue gas. The efficiency of the combustion process can be seen, for example, in the CO concentrations (Nussbaumer, 2017), which were below 100 mg Nm−3 (dry 6 % oxygen), and in the low concentrations of BC in the flue gas (Bond et al., 2013); the combustion of wood pellets produced BC of 0.11–0.18 ng MJ−1 in the flue gas before the BHF, which was approximately 0.1 % of the total mass of produced sub-micron particles. In addition, we observed high efficiency of the combustion in low flue gas concentrations of semi-volatile compounds, and the effective densities of flue gas particles observed in this study (1.9–2.6 g cm−3) can be seen as an indicator of that; for example, Löndahl et al. (2008) linked the low effective density of flue gas particles (1.0 g cm−3, close to the effective density of soot or BC) with the incomplete combustion process and particles having a higher effective density (2.1 g cm−3, close to the density of compounds forming ash particles) with complete combustion. Thus, by means of technological development, the emissions from combustion processes can be minimized (see e.g., Niemelä et al., 2022; Ciupek and Nadolny, 2024), which can lead to significant benefits from a flue gas emissions point of view.

Our experiments showed very clearly that the filtration of flue gas is crucial before the flue gas enters into the atmosphere, and, in more detail, the bag-house filtration used in this study is a sufficient method for that. Importantly, the BHF removed particles from all particle sizes, and it completely removed the smallest particles. This can be seen to be beneficial regarding the health impacts of aerosol emissions because the smallest particles can efficiently deposit into human lungs and affect health. However, our observation that the flue gas velocity affected filtration efficiency demonstrates that the filtration should be carefully designed to obtain maximum benefits from flue gas cleaning.

In general, the transition from fossil fuels to renewable energy sources can include risks with respect to air quality and the climate. One risk that can be seen is related to the emissions of BC, which deteriorates air quality and simultaneously affects global warming by directly absorbing light into the atmosphere and through indirect effects, such as effects on cloud formation and on snow and ice albedo changes. There is a risk that, when the highly optimized fossil fuel technologies are replaced by new ones utilizing more heterogeneous biomass-based fuels, BC emissions from the large-scale production of power and heat increase. Although this risk was not realized at all in the studied heating plant (the BC concentration in the flue gas was below the detection limit of sensitive measurements), this possibility should be kept in mind in all future investment projects; this way, the BC emissions do not cancel the climate benefits of renewable fuels.

In our experiment, the absence of semi-volatile compounds before the BHF and low total hydrocarbon concentrations after the BHF were in line with the observation that the flue gas potential to cause SOA in the atmosphere was relatively low when compared with the primary particle concentrations before the BHF, the SOA potential of small-scale wood combustion (Ihalainen et al., 2019; Hartikainen et al., 2020), or SOA potential of vehicle exhausts (Gordon et al., 2014; Timonen et al., 2017). However, at 100 % load, the SOA potential of flue gas was 3 orders of magnitude larger than the primary PM1 after the BHF. Thus, in emission evaluations of large-scale power plants, the SOA potential of flue gas should be considered when all emission impacts need to be understood. Furthermore, the inorganic compounds of flue gas can contribute to the atmospheric secondary aerosol formation. In this study, we observed this, especially regarding nitrogen compounds; nitrates dominated the secondary aerosol mass when the flue gas sample was treated with an oxidation flow reactor. Nitrate formation is dependent on the NOx levels of the exhaust gas and could thus probably be reduced with technologies decreasing NOx. This highlights the role of NOx (as the nitrate precursor) reduction in future emission reduction systems, which can be done, e.g., by means of selective catalytic reduction (SCR) or selective non-catalytic reduction (SNCR). However, removal of NOx can generate other compounds that affect secondary aerosol emissions, such as ammonia. It should also be noted that the monitoring of NOx emissions of large-scale heat and power plants can be conducted relatively easily and that NOx belongs to the regulated emissions. However, SOA precursor monitoring is not directly included in the emission regulations, and industrially relevant monitoring methodologies do not yet exist.

In a study measuring Hg emissions from a coal-fired power plant in Helsinki (Saarnio et al., 2014), the average mass concentration of Hg was 1.5 ± 0.08 µg Nm−3, measured from the smokestack. In our study, the measured Hg concentration was only a fraction (11 %–17 %) of that. There has been growing interest in regulating the emissions of Hg in the EU, and, in 2017, the Commission Implementing Decision for large combustion plants (LCPs) was established (EU, 2017). In this LCP-BREF document (Best Available Techniques Reference Documents for LCPs), BAT (best available techniques)-associated emission levels (BAT-AELs) were given for coal, lignite, solid biomass, and peat. For coal, the BAT-AELs are < 1–3 and < 1–9 µg Nm−3 for new and existing plants, with a total rated thermal input of < 300 MW, respectively. However, for solid biomass, the BAT-AEL is given as a range of < 1–5 µg Nm−3. The measured values are only 3 %–5 % of the BAT-AEL for the solid biomass of the upper level and 17 %–25 % for that of the lower level. Compared to the ambient concentration of 1.5 ng m−3 typically observed in Helsinki (Kyllönen et al., 2014), 110–170 times higher Hg concentrations were measured in the flue gas, indicating high enrichment in the pellets but still significantly lower concentrations than in the coal. However, due to the dilution of flue gases in the atmosphere, the observed flue gas concentrations of Hg may not contribute significantly to urban air quality.

Due to ambitious climate goals, it is likely that biomass-based fuels will substitute fossil fuels in combustion-based energy production, especially in heating plants. This study presents the gaseous and particle emissions from a large-scale (100 MW) modern heating plant fueled by wood pellets. In this article, we described the results from comprehensive physical and chemical characterization of flue gas particulate matter before and after the flue gas filtration system; measurements included BC, particle number and mass concentration, particle size distributions, volatility measurements, detailed online chemical characterization of submicron particles, and the determination of flue gas potential to form secondary aerosols. We also presented the regulated emissions (CO, SO2, NOx, and dust). In addition to atmospheric emissions, we described the important role of flue gas filtration in emission mitigation.

Climate change mitigation and actions geared toward cleaner air require a lot of knowledge related to aerosol emissions in the atmosphere. However, we noticed a large knowledge gap regarding the emissions from large-scale power and heating plants. Based on comprehensive characterization, this study shows that atmospheric CO2 and BC emission levels from the studied large-scale modern heating plant were low due to the efficient combustion and efficient flue gas filtration. Thus, results indicate that the biomass combustion in energy and heat production can be done in a climate-neutral way with respect to these two most important climate forcers. Although the primary emissions were really low, we found that the potential for secondary aerosol formation from flue gas compounds was relatively high; based on our study, PM1 concentrations can increase by a factor of 1000 during the atmospheric aging of the flue gas.

The results from the study are important for scientific communities working with energy, air quality (see, e.g., WHO, 2021), and climate issues, as well as for authorities and municipalities in charge of energy production and air quality management. We think that these results are a valuable addition to emission inventories and climate models as in-depth information about power plant emissions is very limited in the scientific literature. In addition, we expect that the results can also be utilized by energy companies developing climate-neutral solutions, clean-technology companies delivering solutions (e.g., for flue gas cleaning systems), and politicians aiming to develop future legislation toward climate-neutrality goals. On the other hand, the study highlights the need for further evaluation of power plant emissions, especially regarding the secondary aerosol formation from the precursors emitted by large-scale power and heat production.

Data are available upon request from the corresponding author.

The supplement related to this article is available online at https://doi.org/10.5194/ar-4-23-2026-supplement.

FM: conceptualization, methodology, investigation, formal analysis, writing (original draft), project administration. NK: conceptualization, methodology, investigation, writing (original draft), project administration. MA: methodology, investigation, formal analysis, writing (original draft). TL: investigation, writing (review and editing). PH: investigation, writing (review and editing). LS: investigation, writing (review and editing). LM: investigation, writing (review and editing). PK: investigation, writing (review and editing). JK: investigation, writing (review and editing). SH: investigation, formal analysis, writing (review and editing). KK: investigation, writing (review and editing). SS: investigation, writing (review and editing). KJ: investigation, writing (review and editing). JA: investigation, writing (review and editing). MP: investigation, resources, writing (review and editing). JV: investigation, writing (review and editing). AH: investigation, resources, writing (review and editing). HT: conceptualization, methodology, resources, writing (original draft), supervision, project administration, funding acquisition. TR: conceptualization, methodology, resources, writing (original draft), supervision, project administration, funding acquisition.

At least one of the (co-)authors is a member of the editorial board of Aerosol Research. The peer-review process was guided by an independent editor, and the authors also have no other competing interests to declare.

Publisher's note: Copernicus Publications remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims made in the text, published maps, institutional affiliations, or any other geographical representation in this paper. The authors bear the ultimate responsibility for providing appropriate place names. Views expressed in the text are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the publisher.

We acknowledge the Nessling, the BC Footprint project funded by Business Finland, HSY, the City of Tampere, and several Finnish companies, the Research Council of Finland (Atmosphere and Climate Competence Center, ACCC) for support, and Henna Lintusaari for support in the measurements.

This research has been supported by the Business Finland (grant nos. 530/31/2019 and 528/31/2019); the Research Council of Finland, Luonnontieteiden ja Tekniikan Tutkimuksen Toimikunta (grant nos. 337552 and 337551); and the Maj ja Tor Nesslingin Säätiö.

This paper was edited by Christof Asbach and reviewed by two anonymous referees.

Amanatidis, S., Ntziachristos, L., Giechaskiel, B., Katsaounis, D., Samaras, Z., and Bergmann, A.: Evaluation of an oxidation catalyst (“catalytic stripper”) in eliminating volatile material from combustion aerosol, J. Aerosol Sci., 57, 144–155, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaerosci.2012.12.001, 2013.

Bloomberg: New Energy Outlook 2019, https://about.bnef.com/new-energy-outlook/#toc-download (last access: 22 September 2020), 2020.

Bond, T. C., Doherty, S. J., Fahey, D. W., Forster, P. M., Berntsen, T., DeAngelo, B. J., Flanner, M. G., Ghan, S., Kärcher, B., Koch, D., Kinne, S., Kondo, Y., Quinn, P. K., Sarofim, M. C., Schultz, M. G., Schulz, M., Venkataraman, C., Zhang, H., Zhang, S., Bellouin, N., Guttikunda, S. K., Hopke, P. K., Jacobson, M. Z., Kaiser, J. W., Klimont, Z., Lohmann, U., Schwarz, J. P., Shindell, D., Storelvmo, T., Warren, S. G., and Zender, C. S.: Bounding the role of black carbon in the climate system: A scientific assessment, J. Geophys. Res.-Atmos., 118, 5380–5552, https://doi.org/10.1002/jgrd.50171, 2013

Chandrasekaran, S., Hopke, P., Rector, L., Allen, G., and Lin, L.: Chemical Composition of Wood Chips and Wood Pellets, Energ. Fuel., 26, 4932–4937, https://doi.org/10.1021/ef300884k, 2012.

Ciupek, B. and Nadolny, Z.: Emission of Harmful Substances from the Combustion of Wood Pellets in a Low-Temperature Burner with Air Gradation: Research and Analysis of a Technical Problem, Energies, 17, 3087, https://doi.org/10.3390/en17133087, 2024.

Czech, H., Pieber, S. M., Tiitta, P., Sippula, O., Kortelainen, M., Lamberg, H., Grigonyte, J., Streibel, T., Prévôt, A. S. H., Jokiniemi, J., and Zimmermann, R.: Time-resolved analysis of primary volatile emissions and secondary aerosol formation potential from a small-scale pellet boiler, Atmos. Environ., 158, 236–245, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.atmosenv.2017.03.040, 2017.

Drinovec, L., Močnik, G., Zotter, P., Prévôt, A. S. H., Ruckstuhl, C., Coz, E., Rupakheti, M., Sciare, J., Müller, T., Wiedensohler, A., and Hansen, A. D. A.: The “dual-spot” Aethalometer: an improved measurement of aerosol black carbon with real-time loading compensation, Atmos. Meas. Tech., 8, 1965–1979, https://doi.org/10.5194/amt-8-1965-2015, 2015.

EU: Commission Implementing Decision (EU) 2017/1442 of 31 July 2017 establishing best available techniques (BAT) conclusions, under Directive 2010/75/EU of the European Parliament and of the Council, for large combustion plants, Official Journal of the European Union, https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=CELEX%3A32017D1442 (last access: 28 January 2026), 2017.

Gordon, T. D., Presto, A. A., May, A. A., Nguyen, N. T., Lipsky, E. M., Donahue, N. M., Gutierrez, A., Zhang, M., Maddox, C., Rieger, P., Chattopadhyay, S., Maldonado, H., Maricq, M. M., and Robinson, A. L.: Secondary organic aerosol formation exceeds primary particulate matter emissions for light-duty gasoline vehicles, Atmos. Chem. Phys., 14, 4661–4678, https://doi.org/10.5194/acp-14-4661-2014, 2014.

Guevara, M., Enciso, S., Tena, C., Jorba, O., Dellaert, S., Denier van der Gon, H., and Pérez García-Pando, C.: A global catalogue of CO2 emissions and co-emitted species from power plants, including high-resolution vertical and temporal profiles, Earth Syst. Sci. Data, 16, 337–373, https://doi.org/10.5194/essd-16-337-2024, 2024.

Hartikainen, A., Tiitta, P., Ihalainen, M., Yli-Pirilä, P., Orasche, J., Czech, H., Kortelainen, M., Lamberg, H., Suhonen, H., Koponen, H., Hao, L., Zimmermann, R., Jokiniemi, J., Tissari, J., and Sippula, O.: Photochemical transformation of residential wood combustion emissions: dependence of organic aerosol composition on OH exposure, Atmos. Chem. Phys., 20, 6357–6378, https://doi.org/10.5194/acp-20-6357-2020, 2020.

Hays, M. D., Kinsey, J., George, I., Preston, W., Singer, C., and Patel, B.: Carbonaceous Particulate Matter Emitted from a Pellet-Fired Biomass Boiler, Atmosphere, 10, 536, https://doi.org/10.3390/atmos10090536, 2019.

Heringa, M. F., DeCarlo, P. F., Chirico, R., Tritscher, T., Dommen, J., Weingartner, E., Richter, R., Wehrle, G., Prévôt, A. S. H., and Baltensperger, U.: Investigations of primary and secondary particulate matter of different wood combustion appliances with a high-resolution time-of-flight aerosol mass spectrometer, Atmos. Chem. Phys., 11, 5945–5957, https://doi.org/10.5194/acp-11-5945-2011, 2011.

IEA: World energy outlook 2019, 2020, The International Energy Agency (IEA), https://www.iea.org/reports/world-energy-outlook-2019 (last access: 21 September 2020).

Ihalainen, M., Tiitta, P., Czech, H., Yli-Pirilä, P., Hartikainen, A., Kortelainen, M., Tissari, J., Stengel, B., Sklorz, M., Suhonen, H., Lamberg, H., Leskinen, A., Kiendler-Scharr, A., Harndorf, H., Zimmermann, R., Jokiniemi, J., and Sippula, O.: A novel high-volume Photochemical Emission Aging flow tube Reactor (PEAR), Aerosol Sci. Tech., 53, 276–294, https://doi.org/10.1080/02786826.2018.1559918, 2019.

Jiang, K., Xing, R., Luo, Z., Huang, W., Yi, F., Men, Y., Zhao, N., Chang, Z., Zhao, J., Pan, B., and Shen, G.: c Pollutant emissions from biomass burning: A review on emission characteristics, environmental impacts, and research perspectives, Particuology, 85, 296–309, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.partic.2023.07.012, 2024.

Jimenez, J. L., Canagaratna, M. R., Donahue, N. M., Prevôt, A. S. H., Zhang, Q., Kroll, J. H., Decarlo, P. F., Allan, J. D., Coe, H., Ng, N. L., Aiken, A. C., Ulbrich, I. M., Grieshop, A. P., Duplissy, J., Wilson, K. R., Lanz, V. A., Hueglin, C., Sun, Y. L., Tian, J., Laaksonen, A., Raatikainen, T., Rautiainen, J., Vaattovaara, P., Ehn, M., Kulmala, M., Tomlinson, J. M., Cubison, M. J., Dunlea, E. J., Alfarra, M. R., Williams, P. I., Bower, K., Kondo, Y., Schneider, J., Drewnick, F., Borrmann, S., Weimer, S., Demerjian, K., Salcedo, D., Cottrell, L., Takami, A., Miyoshi, T., Shimono, A., Sun, J. Y., Zhang, Y. M., Dzepina, K., Sueper, D., Jayne, J. T., Herndon, S. C., Williams, L. R., Wood, E. C., Middlebrook, A. M., Kolb, C. E., Baltensperger, U., Worsnop, D. R.: Evolution of organic aerosols in the atmosphere, Science, 326, 1525–1529, 2009.

Keskinen, J. and Rönkkö, T.: Can Real-World Diesel Exhaust Particle Size Distribution be Reproduced in the Laboratory? A Critical Review, Journal of the Air and Waste Management Association, 60, 1245–1255, 2010.

Keskinen, J., Pietarinen, K., and Lehtimäki, M.: Electrical low pressure impactor, J. Aerosol Sci., 23, 353–360, 1992.

Kyllönen, K., Hakola, H., Hellén, H., Korhonen, M., and Verta, M.: Atmospheric mercury fluxes in southern boreal forest and wetland, Water Air Soil Poll., 223, 1171–1182, 2012.

Kyllönen, K., Paatero, J., Aalto, T., and Hakola, H.: Nationwide survey of airborne mercury in Finland, Boreal Environ. Res., 19, 355–367, 2014.

Lamberg, H., Sippula, O., Tissari, J., and Jokiniemi, J.: Effect of Air Staging and Load in Fine-Particle and Gaseous Emissions from a Small-Scale Pellet Boiler, Energ. Fuel., 25, 4952–4960, 2011.

Lepistö, T., Lintusaari, H., Oudin, A., Barreira, L. M. F., Niemi, J. V., Karjalainen, P., Salo, L., Silvonen, V., Markkula, L., Hoivala, J., Marjanen, P., Martikainen, S., Aurela, M., Reyes, F. R., Oyola, P., Kuuluvainen, H., Manninen, H. E., Schins, R. P. F., Vojtisek-Lom, M., Ondracek, J., Topinka, J., Timonen, H., Jalava, P., Saarikoski, S., and Rönkkö, T.: Particle lung deposited surface area (LDSAal) size distributions in different urban environments and geographical regions: Towards understanding of the PM2.5 dose-response, Environ. Int., 180, 108224, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envint.2023.108224, 2023.

Li, R., Palm, B. B., Ortega, A. M., Hlywiak, J., Hu, W., Peng, Z., Day, D. A., Knote, C., Brune, W. H., de Gouw, J. A., and Jimenez, J. L.: Modeling the Radical Chemistry in an Oxidation Flow Reactor: Radical Formation and Recycling, Sensitivities, and the OH Exposure Estimation Equation, J. Phys. Chem. A, 119, https://doi.org/10.1021/jp509534k, 2015.

Löndahl, J., Pagels, J., Boman, C., Swietlicki, E., Massling, A., Rissler, J., Blomberg, A., Bohgard, M., and Sandström, T.: Deposition of Biomass Combustion Aerosol Particles in the Human Respiratory Tract, Inhal. Toxicol., 20, 923–933, https://doi.org/10.1080/08958370802087124, 2008.

Marjamäki, M., Ntziachristos, L., Virtanen, A., Ristimäki, J., Keskinen, J., Moisio, M., Palonen, M., and Lappi, M.: Electrical filter stage for the ELPI, SAE Technical paper, 2002–01-0055, SAE International, 2002.

Mertens, J., Lepaumier, H., Rogiers, P., Desagher, D., Goossens, L., Duterque, A., Le Cadre, E., Zarea, M., Blondeau, J., and Webber, M.: Fine and ultrafine particle number and size measurements from industrial combustion processes: Primary emissions field data, Atmos. Pollut. Res., 11, 803–814, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apr.2020.01.008, 2020.

Mikkanen, P., Moisio, M., Keskinen, J., Ristimäki, J., and Marjamäki, M.: Sampling method for particle measurements of vehicle exhaust, SAE International, SAE Tech. Pap. Ser. 2001, No. 2001-01-0219, https://doi.org/10.4271/2001-01-0219, 2001.

Mylläri, F., Asmi, E., Anttila, T., Saukko, E., Vakkari, V., Pirjola, L., Hillamo, R., Laurila, T., Häyrinen, A., Rautiainen, J., Lihavainen, H., O'Connor, E., Niemelä, V., Keskinen, J., Dal Maso, M., and Rönkkö, T.: New particle formation in the fresh flue-gas plume from a coal-fired power plant: effect of flue-gas cleaning, Atmos. Chem. Phys., 16, 7485–7496, https://doi.org/10.5194/acp-16-7485-2016, 2016.

Mylläri, F., Pirjola, L., Lihavainen, H., Asmi, E., Saukko, E., Laurila, T., Vakkari, V., O'Connor, E., Rautiainen, J., Häyrinen, A., Niemelä, V., Maunula, J., Hillamo, R., Keskinen, J., and Rönkkö, T.: Characteristics of particle emissions and their atmospheric dilution during co-combustion of coal and wood pellets in a large combined heat and power plant, Journal of the Air & Waste Management Association, 69, 97–108, https://doi.org/10.1080/10962247.2018.1521349, 2019.

Niemelä, N. P., Mylläri, F., Kuittinen, N., Aurela, M., Helin, A., Kuula, J., Teinilä, K., Nikka, M., Vainio, O., Arffman, A., Lintusaari, H., Timonen, H., Rönkkö, T., and Joronen, T.: Experimental and numerical analysis of fine particle and soot formation in a modern 100 MW pulverized biomass heating plant, Combust. Flame, 240, 111960, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.combustflame.2021.111960, 2022.

Ntziachristos, L., Giechaskiel, B., Pistikopoulos, P., Samaras, Z., Mathis, U., Mohr, M., Ristimäki, J., Keskinen, J., Mikkanen, P., Casati, R., Scheer, V., and Vogt, R.: Performance evaluation of a novel sampling and measurement system for exhaust particle characterization, in: SAE 2004 World Congress and Exhibition, 14 January 2004, Detroit, USA, https://doi.org/10.4271/2004-01-1439, 2004.

Nussbaumer, T.: Aerosols from Biomass Combustion, Technical report on behalf of the IEA Bioenergy Task 32, IEA Bioenergy, https://task32.ieabioenergy.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/07/Nussbaumer_IEA_T32_Aerosol-Report_2017_07_14.pdf (last access: 28 Janaury 2026), July 2017.

Onasch, T. B., Trimborn, A., Fortner, E. C., Jayne, J. T., Kok, G. L., Williams, L. R., Davidovits, P., and Worsnop, D. R.: Soot Particle Aerosol Mass Spectrometer: Development, Validation, and Initial Application, Aerosol Sci. Tech., 46, 804–817, https://doi.org/10.1080/02786826.2012.663948, 2012.

Ortega, A. M., Day, D. A., Cubison, M. J., Brune, W. H., Bon, D., de Gouw, J. A., and Jimenez, J. L.: Secondary organic aerosol formation and primary organic aerosol oxidation from biomass-burning smoke in a flow reactor during FLAME-3, Atmos. Chem. Phys., 13, 11551–11571, https://doi.org/10.5194/acp-13-11551-2013, 2013.

Pirjola, L., Niemi, J. V., Saarikoski, S., Aurela, M., Enroth, J., Carbone, S., Saarnio, K., Kuuluvainen, H., Kousa, A., Rönkkö, T., and Hillamo, R.: Physical and chemical characterization of urban winter-time aerosols by mobile measurements in Helsinki, Finland, Atmos. Environ., 158, 60–75, 2017.

Ristimäki, J., Virtanen, A., Marjamäki, M., Rostedt, A., and Keskinen, J.: On-line measurement of size distribution and effective density of submicron aerosol particles, J. Aerosol Sci., 33, 1541–1557, 2002.

Robinson, A. L., Donahue, N. M., Shrivastava, M. K., Weitkamp, E. A., Sage, A. M., Grieshop, A. P., Lane, T. E., Pierce, J. R., and Pandis, S. N.: Rethinking Organic Aerosols: Semivolatile Emissions and Photochemical Aging, Science, 315, 1259–1262, 2007.

Rönkkö, T. and Timonen, H.: Overview of Sources and Characteristics of Nanoparticles in Urban Traffic-Influenced Areas, J. Alzheimers Dis., 72, 15–28, https://doi.org/10.3233/JAD-190170, 2019.

Rönkkö, T., Virtanen, A., Vaaraslahti, K., Keskinen, J., Pirjola, L., and Lappi, M.: Effect of dilution conditions and driving parameters on nucleation mode particles in diesel exhaust: laboratory and on-road study, Atmos. Environ., 40, 2893–2901, 2006.

Rönkkö, T., Kuuluvainen, H., Karjalainen, P., Keskinen, J., Hillamo, R., Niemi, J. V., Pirjola, L., Timonen, H. J., Saarikoski, S., Saukko, E., Järvinen, A., Silvennoinen, H., Rostedt, A., Olin, M., Yli-Ojanperä, J., Nousiainen, P., Kousa, A., and Dal Maso, M.: Traffic is a major source of atmospheric nanocluster aerosol, P. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA, 114, 7549–7554, https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1700830114, 2017.

Saarnio, K., Frey, A., Niemi, J., Timonen, H., Rönkkö, T., Karjalainen, P., Vestenius, M., Teinilä, K., Pirjola, L., Niemelä, V., Keskinen, J., Häyrinen, A., and Hillamo, R.: Chemical composition and size of particles in emissions of a coal-fired power plant with flue gas desulfurization, J. Aerosol Sci., 73, 14–26, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaerosci.2014.03.004, 2014.

Schmidt, G., Trouvé, G., Leyssens, G., Schönnenbeck, C., Genevray, P., Cazier, F., Dewaele, D., Vandenbilcke, C., Faivre, E., Denance, Y., and Le Dreff-Lorimier, C.: Wood washing: Influence on gaseous and particulate emissions during wood combustion in a domestic pellet stove, Fuel Process. Technol., 174, 104–117, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.fuproc.2018.02.020, 2018.

Simonen, P., Saukko, E., Karjalainen, P., Timonen, H., Bloss, M., Aakko-Saksa, P., Rönkkö, T., Keskinen, J., and Dal Maso, M.: A new oxidation flow reactor for measuring secondary aerosol formation of rapidly changing emission sources, Atmos. Meas. Tech., 10, 1519–1537, https://doi.org/10.5194/amt-10-1519-2017, 2017.

Sippula, O., Hytönen, K., Tissari, J., Raunemaa, T., and Jokiniemi, J.: Effect of Wood Fuel on the Emissions from a Top-Feed Pellet Stove, Energ. Fuel., 21, 1151–1160, https://doi.org/10.1021/ef060286e, 2007.

Sippula, O., Hokkinen, J., Puustinen, H., Yli-Pirilä, P., and Jokiniemi, J.: Particle Emissions from Small Wood-Fired District Heating Units, Energ. Fuel., 23, 2974–2982, https://doi.org/10.1021/ef900098v, 2009a.

Sippula, O., Hokkinen, J., Puustinen, H., Yli-Pirilä, P., and Jokiniemi, J.: Comparison of particle emissions from small heavy fuel oil and wood fired boilers, Atmos. Environ., 43, 4855–4864, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.atmosenv.2009.07.022, 2009b.

Sippula, O., Hokkinen, J., Puustinen, H., Yli-Pirilä, P., and Jokiniemi, J.: Particle emissions from small biomass and fuel oil fired heating units, in: 17th European Biomass Conference & Exhibition, Proceeding of the International Conference held in Hamburg, Germany, 1329–1337, ISBN 978-88-89407-57-3, 2009c.

Statistics of Finland: Fuel Classification 2019, https://www.stat.fi/en/luokitukset/polttoaineet/polttoaineet_1_20190101/ (last access: 14 September 2020), 2019.

Stevens, R. G., Pierce, J. R., Brock, C. A., Reed, M. K., Crawford, J. H., Holloway, J. S., Ryerson, T. B., Huey, L. G., and Nowak, J. B.: Nucleation and growth of sulfate aerosol in coal-fired power plant plumes: sensitivity to background aerosol and meteorology, Atmos. Chem. Phys., 12, 189–206, https://doi.org/10.5194/acp-12-189-2012, 2012.

Strand, M., Pagels, J., Szpila, A., Gudmundsson, A., Swietlicki, E., Bohgard, M., and Sanati, M.: Fly Ash Penetration through Electrostatic Precipitator and Flue Gas Condenser in a 6 MW Biomass Fired Boiler, Energ. Fuel., 16, 1499–1506, https://doi.org/10.1021/ef020076b, 2002.

Timonen, H., Karjalainen, P., Saukko, E., Saarikoski, S., Aakko-Saksa, P., Simonen, P., Murtonen, T., Dal Maso, M., Kuuluvainen, H., Bloss, M., Ahlberg, E., Svenningsson, B., Pagels, J., Brune, W. H., Keskinen, J., Worsnop, D. R., Hillamo, R., and Rönkkö, T.: Influence of fuel ethanol content on primary emissions and secondary aerosol formation potential for a modern flex-fuel gasoline vehicle, Atmos. Chem. Phys., 17, 5311–5329, https://doi.org/10.5194/acp-17-5311-2017, 2017.

Wang, K., Nakao, S., Thimmaiah, D., and Hopke, P. K.: Emissions from in-use residential wood pellet boilers and potential emissions savings using thermal storage, Sci. Total Environ., 676, 564–576, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2019.04.325, 2019.

Wang, S. C. and Flagan, R. C.: Scanning Electrical Mobility Spectrometer, Aerosol Sci. Tech., 13, 230–240, https://doi.org/10.1080/02786829008959441, 1990.

WHO: WHO Global Air Quality Guidelines: Particulate Matter (PM2.5 and PM10), Ozone, Nitrogen Dioxide, Sulfur Dioxide and Carbon Monoxide, World Health Organization, https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/345329 (last access: 28 January 2025), 2021.

Yli-Ojanperä, J., Kannosto, J., Marjamäki, M., and Keskinen, J.: Improving the Nanoparticle Resolution of the ELPI, Aerosol Air Qual. Res., 10, 360–366, https://doi.org/10.4209/aaqr.2009.10.0060, 2010.